Friday, 4:37pm

26 February 2010

Back to the future

Day two at the ‘Decoding the digital’ conference at the V&A

Day two of the ‘Decoding the Digital’, conference at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, kicked off with a change of scene, writes Liz Farrelly.

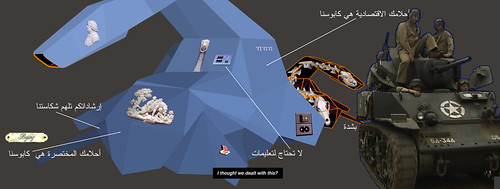

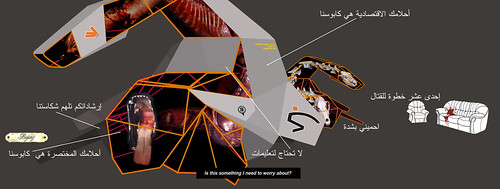

Graphic design, branding and advertising were centre stage, with filmmaker Johnny Hardstaff in conversation with Shane Walter of onedotzero. Here was the first mention of gaming, as Hardstaff showed extracts from his two short ‘manifesto’ movies, History of Gaming and Future of Gaming, the second of which was commissioned by Sony Playstation in 2001. Trained as a print designer, Hardstaff revealed how he’d pushed the limits of available software, making movies using Photoshop. He suggested that software upgrades are prompted by such experiments (Photoshop now includes animation functions).

Below: Wedgewood and gore – frames from Future of Gaming by Johnny Hardstaff.

Hardstaff’s dystopian ‘future’ shocked and awed his commercial patrons, who publicly distanced themselves from the movie, while off the record, ‘they loved it’. The irony was glaring; a major corporation, which facilitates ultra violence in the form of ‘shoot ‘em up’ games, was reluctant to validate a fictionalised account of the games industry that revealed undercurrents of control and exploitation. The fact that those clients ‘paid very little’, but allowed Hardstaff to retain copyright, meant the movie became his calling card, parlayed into subsequent commercial collaborations. He added; ‘Advertising is imploding in a delicious way, where consumers are actually getting what they want and artists are getting to do their own thing’. The message being, use this new patronage for your own ends.

In the question session, Hardstaff pointed out that gaming owes its origins to missile tracking systems, adding; ‘I’m on the cusp of finding it repellent and exciting…I like to take the visual language of systems that people in power use and wield them myself’. Charlie Gere added that Hardstaff’s movies were not simply representation, but ‘a new way of constructing meaning’. Hardstaff explained his method as ‘collating, collage, sampling and feedback’, labelling it ‘Craft Plus’.

Casey Reas (above), of UCLA’s Department of Design Media Arts, and another ‘Decode’ exhibitor, explained Processing, which he developed in partnership with Ben Fry in 2001. (See Eye 65.) A a show of hands revealed that this simple-to-use, open-source language had been used by the majority of the audience. Reas uses it to ‘develop my own world, with no relationship to the worlds we know’. To disseminate this DIY language to an ever-wider audience, though, he’s using good old-fashioned book publishing, and writing increasingly easier instructions, with the aim that perhaps one day coding will be the new literacy.

During questions, Reas elaborated on an earlier point; how do you choose one image to exhibit from the multiple, drawn iterations of an algorithm? He suggested that the looping and phasing of computer-generated imagery is closer to the performance of a musical score than a unique work of art, declaring: ‘I relate more to musicians than to visual artists.’

Karsten Schmidt followed, thanking Reas for ‘Processing’, which he’s incorporated into a palette of software used to create moving, interactive imagery, including the identity for ‘Decode: Digital Design Sensation’ (see Eye 74). He talked about how design is moving from ‘objects to operations’. Questioned as to why ‘all this ‘art’ looks beautiful, where is the ‘bad’?’, curator Louise Shannon declared that ‘data can be troubling, unnerving’, while Schmidt pointed out; ‘…this is so young, we’re only scratching the surface of what’s possible’. Again, music was mentioned, as ‘evoking more powerful emotions, while art evokes aesthetics; no painting ever affected me like music does, but this (meaning computer art) could reach the same impact’, declared Schmidt

Next, curators Louise Shannon and Shane Walter, took the stage to discuss the long and involved process of staging the exhibition, ‘Decode: Digital Design Sensation’. Walter went on to describe the work of onedotzero, which he co-founded in the mid 1990s. A hybrid of travelling film festival and ‘culture club’, onedotzero has brought digital creativity to a worldwide audience, far beyond the art ghetto.

This is unashamedly entertaining! And while successive speakers had asked, ‘what is the cathedral of this new art form’, Walter dared to suggest it may be U2’s stadium tour stage set (commissioned from onedotzero industries), which pulsated with interactive, reactive lights forming and reforming into pattern and image. The achievement of onedotzero poses a fundamental question; these digital displays evoke the notion of spectacle, so perhaps judging it in relation to art, the understanding of which demands contemplation and perhaps translation, is missing the point. Instead, this works on the body and the senses, offering new experiences; in short, it awes.

Beryl Graham is Professor of New Media Art at the University of Sunderland, and a member of CRUMB (Curatorial Resource for Upstart Media Bliss), and she brought us up to date with innovative initiatives, back in the art ghettos. Her remit is to help curators understand computer art, the better to judge, exhibit and promote it; ‘if they can understand the process of bronze casting, they can understand the technical details of code’. Going back to the 1970s she revealed how what was once deemed beyond the pale, and therefore not to be shared with art audiences, was later reconsidered, and proved popular. Interactivity in galleries is fundamentally feared though, as ‘participation is beautiful, but it’s difficult…it’s out of control’. If interactivity tests institutions, and the evidence shows that the worst didn’t happen, then, she suggests, the rules will change.

Changing rules were explored further by Hannah Reddler, the Science Museum’s resident art curator. Since 1997 she’s facilitated more than 70 commissions of computer art projects, much of which were initially considered ‘display material’. She’s managed, however, to ‘collect’ many of those commissions by lobbying for changes to ‘accession politics’. Now those commissions will be conserved, and once protected, may be re-exhibited in the future. But, she pointed out, artists aren’t always co-operative when it comes to extending the longevity of an artwork, ‘they don’t necessarily want to rewrite code for new systems software’. She suggested that computer art should be collected, ‘as an animal, not an object’, meaning, constant care is needed, rather than simply wrapping it in cotton wool and storing it in an acid-free box. So, the Science Museum has instigated Team Media, a cross-departmental initiative to audit the components of each artwork so it may be ‘re-ignited’. They’ve also recognised that asking artists to write bespoke software provides better insurance against obsolescence.

The last speaker, Bruce Wands of New York Digital Salon, and Chair of the MFA in Computer Art at the School of Visual Arts, sees a future where the word ‘digital’ is submerged, where even more new art forms will mix with traditional means, and it all just becomes art, again. The ‘art space’ though will have expanded beyond even the art and design divide, to become embedded in our homes and cities; much like onedotzero’s immersive / experiential approach, perhaps. He’s basing his predictions on ‘34 years of research’, having logged the evolution of computer art and design across higher education, cultural institutions and the commercial realm (see image at top).

So, the elephant in the room was finally addressed. Dropping the word ‘computer’ implies that this work be judged on a level playing field, as art or design. But it’s evident that those judging it need to understand how it is made, the processes, the context, and the issues unique to this form. So for now, keep the nomenclature, so as to identity that need for more scholarship and understanding.

Below: Roman Verostko. Photo by Francesca Franco, www.francescafranco.net.

Verostko’s career gives a clue as to why, at this conference, there was a fascination with the algorithm. The first generation of computer artists worked simultaneous to Abstraction. And although, much of that early work was often exhibited alongside a set of written instructions or even code (which would place it closer to Conceptual Art), appreciation of the surface – colour and pattern – appeared to take precedence over an understanding of the method of production.

At times during the conference, I felt as if I’d been transported back to the early 1990s, when fears were being voiced about the role of computers in the design process, principally by graphic designers. Will everything look the same; will we be seduced by surface and image; will content and problem solving be sacrificed? The ‘computer aesthetic’ was celebrated and fetishised in some quarters, but most fears were dispelled, when users realised, it’s just a tool, a more powerful pencil. And the output must be judged, good or bad, just like any other design. Designers are still exploring the possibilities of such a tool, but the fear of losing control to the machine was dispelled, a long time ago. It looks, though, as if those concerns are still being debated in the art world, along with issues regarding display, collecting, crediting (who gets the name check) and the institutional validation of an art form.

Below: day two panel, including curators Shane Walter (third from left) and Louise Shannon (third from right). Top: Bruce Wands’ presentation. Photos by Francesca Franco, www.francescafranco.net.

See also: Liz Farrelly’s Discussing the digital – John Maeda on dirt, de-cluttering and the power of art and The Wm. Morris code – Finding digital roots in the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Special thanks to Francesca Franco, www.francescafranco.net, Research Fellow, Computer Art and Technocultures (CAT), Department of History of Art and Screen Media, Birkbeck College.

A current display at the V&A, ‘Digital Pioneers’ (until 25 April 2010), contains highlights from the collection and provides a historical counterpart to the contemporary V&A exhibition ‘Decode: Digital Design Sensations’ (see ‘Electric Narcissus and digital Echo’).

Eye, the international review of graphic design, is a quarterly journal you can read like a magazine and collect like a book. It’s available from all good design bookshops and at the online Eye shop, where you can order subscriptions, single issues and classic collections of themed back issues.

Eye 74 features a Reputations interview with Karsten Schmidt.