Friday, 2:00pm

17 August 2018

Bridges and verses

John Vernon Lord: Illustrating Joyce and Carroll

House of Illustration, London<br> 13 July - 4 Nov 2018<br>The House of Illustration’s John Vernon Lord exhibition shows Lord’s extraordinary talent for magical narrative

You may be aware of John Vernon Lord’s work as a result of his long career as a freelance illustrator (which began in 1961) or through his lectures at Brighton College of Art, where he has taught illustration for nearly half a century, writes Clare Walters.

Or from his popular and long-lived children’s picturebook, The Giant Jam Sandwich and others, or his artwork for Deep Purple’s album The Book of Taliesyn. But whether you know him or not, the House of Illustration’s exhibition ‘John Vernon Lord: Illustrating Joyce and Carroll’ offers a chance to marvel at this imaginative, mega-competent artist’s extraordinary talent for narrative imagery.

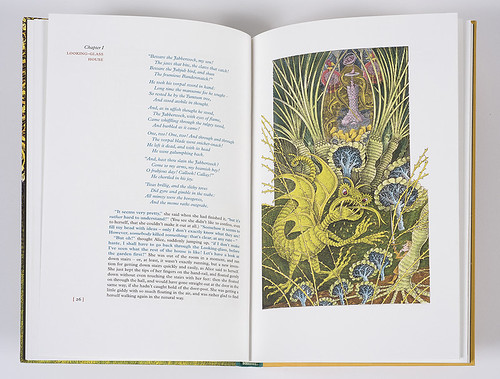

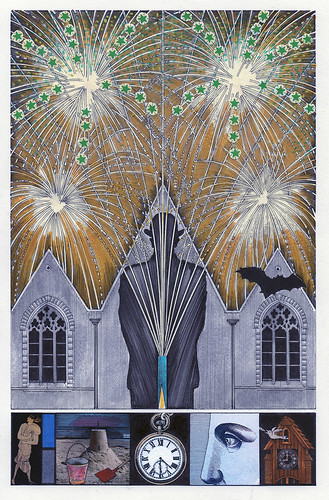

Spread from Alice Through the Looking Glass.

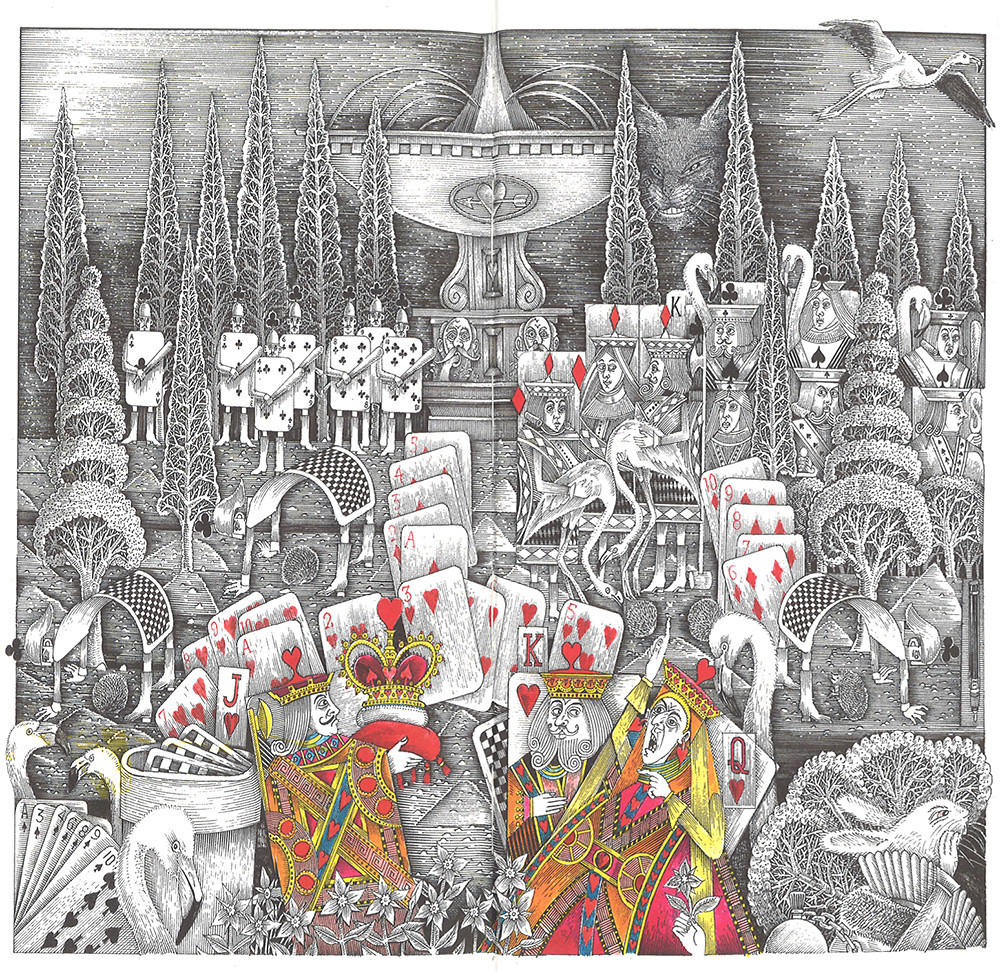

Top: Spread from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

All images © John Vernon Lord.

The show is grouped into several different sections. First there are three sets of illustrations for 21st-century Artists’ Choice Editions of Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark (1876), Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-glass and What Alice Found There (1871). The highly detailed contents of the Carroll pictures reward close viewing. For instance, in ‘The Rabbit Hole’, not only is there an intriguing array of books, maps and objects lining the hole to pore over, but also the powerful perspective draws you as dizzily down as it does Alice. In ‘Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast’ the collection of mesmeric optical illusions is pleasingly perplexing, and in the image of a boss-eyed ‘Humpty Dumpty’ there is an almost-hidden peace symbol to spot disappearing off the edge of the wall. One intriguing aspect of the two Alice books is that the girl herself is not illustrated. Instead her words are set in blue rather than black type, so that her presence is ‘heard’ rather than seen (a fun twist on the phrase ‘children should be seen and not heard’).

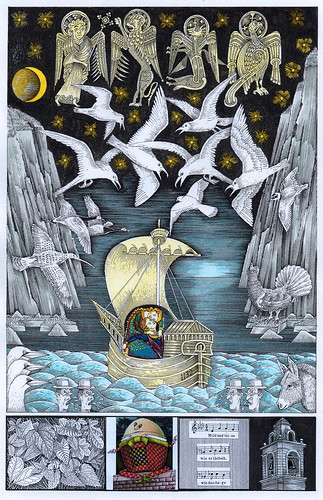

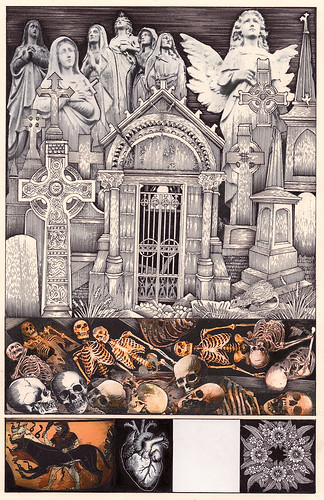

An illustration from Finnegans Wake.

Next there are two sets of illustrations for the Folio Society’s editions of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) and Finnegans Wake (1939). Lord says: ‘My main hope is that the illustrations act as a bridge of communication between the text and the reader.’ To aid this understanding, he has added a ‘bridge’ of smaller images along the bottom of each main illustration to provide a link between the one before and the one after (with the final one returning to the first). This is based on the medieval concept of ‘predellas’ and, Lord says, ‘echoes Joyce’s use of cyclical repetition’. Again hidden in the intricate detail and complex pattern-making are layers of different meanings and references, while some images appeal directly to the emotions, such as the illustration ‘Anna Livia Plurabelle’, which shows a shimmering watery face that looks so real it sends shivers down the spine.

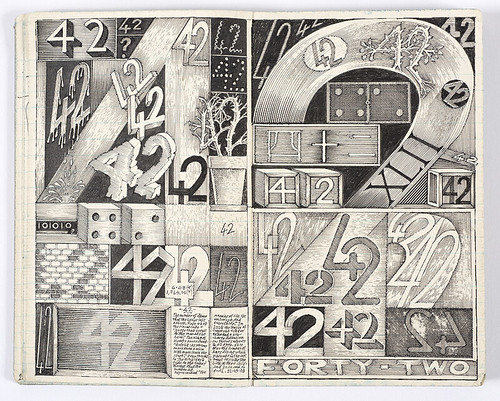

Each set of Carroll and Joyce illustrations is shown with its accompanying notebooks, which are works of art in themselves. In the exhibition booklet Chris Riddell describes Lord as a ‘wizard’, with wizarding gifts and magical spell books. And when you look at the entries in the artist’s notebooks this appears to be more truth than fiction. For each small book is crammed with tiny lines of neat writing, columns of calculations, miniature drawings, recurring motifs such as eyes or clockfaces, complex interweaving patterns, colour samples, numerous lists and so much more. In one, for instance, there is an extraordinary meditation on the number 42 (significant both to Carroll and Douglas Adams, author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy) where the figures ‘4’ and ‘2’ are configured in an assortment of different ways – on dice, 3D shapes, dripping wax, twigs, bricks, dominoes and Roman numerals. This alone is utterly fascinating.

Title 42, from John Vernon Lord’s sketchbook.

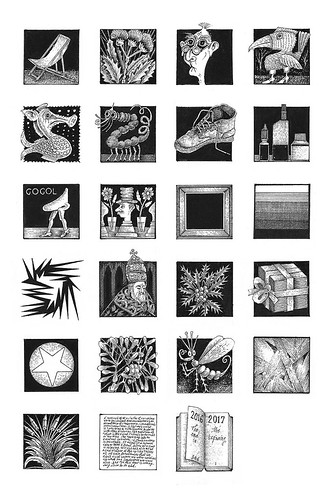

As well as the books, the ‘A Drawing a Day 2016’ series is on display. It shows hundreds of small pen-and-ink drawings, one completed on each day of that year. These witty mini-pictures have a particular charm, as they show weird and wonderful images of anything that took Lord’s fancy on a particular day, from imaginary monsters and creatures to real birds, insects and spiders, to letters of the alphabet and numerals to the more prosaic: pen, scalpel, video remote and even a toilet. Finally there are two large Lord works from the 1960s: The Back Basement of 76 Charlotte Street, W1, April 1962 and Beneath the Tree, 1966.

The December entry for ‘A Drawing a Day 2016’ series.

These illustrations and notebooks suggest a man whose mind is constantly exploding with ideas, thoughts and random (or not) connections, and who combines these with meticulous research, inventive visual experiments and careful documentation to create a kind of magic. But it is a magic that is firmly rooted in the real world, with images often drawn from actual places and objects. Intriguingly, Lord’s precision includes the exact time it takes to do each drawing. Like a good meal, this exhibition is so rich and satisfying it is worth enjoying slowly and savouring each bit.

Illustrations from Ulysses.

Clare Walters, author of children’s picturebooks and journalist, London

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.