Friday, 11:00am

28 February 2014

Design for life

To mark First Things First’s 50th anniversary – an initiative to update the manifesto’s aims for the digital age

If you are not a graphic designer, you are unlikely to have heard of the ‘First Things First’ manifesto, writes Nigel Ball.

When reading either of its two versions, from 1964 and 1999, they could be seen as an extreme case of professional navel-gazing and of no relevance outside of the design community. But a planned update of the manifesto for 2014 is determined to engage a wider audience in the debate about graphic design’s relationship with life and society.

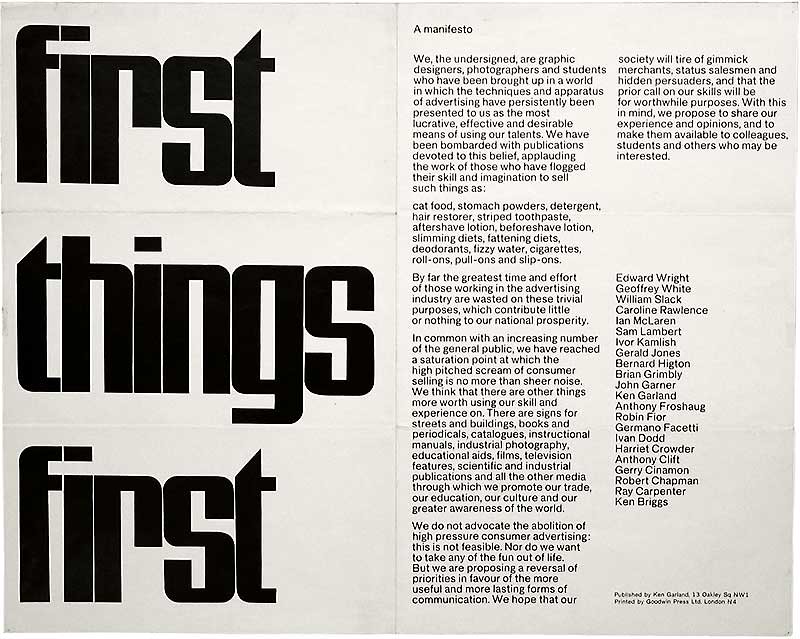

First written and published in 1964 by designer Ken Garland (see Eye 66), ‘First Things First’ questioned the primary focus of graphic design that had become dominated by commercial work. It asked why designers’ time and services could not be put to better use for wider societal gain, citing education and cultural sectors as key areas that could benefit from designers’ skills. Signed by 22 practitioners of the day, the manifesto had Modernist ideology at its core.

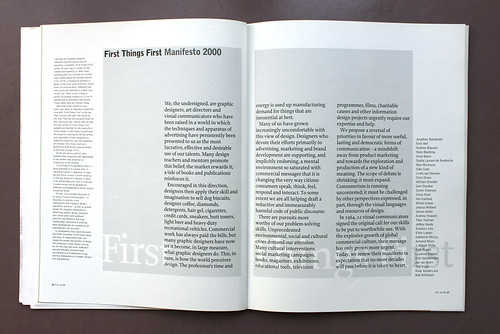

The manifesto was updated in 1999 as ‘First Things First 2000’, instigated by designer Tibor Kalman and the anti-advertising publication Adbusters and published simultaneously in design-related magazines including Eye (see ‘First Things First Manifesto 2000’ in Eye 33), AIGA Journal, Blueprint, Items, Form, Emigre and Adbusters. This text was more aggressive and vehemently against advertising – the 1964 version appeased ‘high pressure consumer advertising’ in its last paragraph, claiming it wanted to alter the priorities of graphic design rather than abolish all commercial activity. ‘First Things First 2000’ took a stronger line:

‘We, the undersigned, are graphic designers, art directors and visual communicators who have been raised in a world in which the techniques and apparatus of advertising have persistently been presented to us as the most lucrative, effective and desirable use of our talents ... Commercial work has always paid the bills, but many graphic designers have now let it become, in large measure, what graphic designers do. This, in turn, is how the world perceives design. The profession’s time and energy is used up manufacturing demand for things that are inessential at best.’

On the eve of the 1964 manifesto’s 50th anniversary, in March 2014, designer Cole Peters has decided it is time to renew ‘First Things First’ once again. Peters first came across both the 1964 and 1999 versions in Manifesto, a small print-run book published in 2010 by Manifesto Project to coincide with an exhibition of design texts. Peters says of the discovery: ‘At the time, I was working as an in-house advertising director for a Canadian retail company, struggling with my increasing distaste for the work I was doing and questioning how I could do something more meaningful; the work was interesting for me … but at the end of the day, it bothered me that it was only truly beneficial in a corporate, profit-centric sense.’ Reading ‘First Things First’ had such an impact on Peters that when he went on to co-found the studio Burdocks in Canada, the studio’s first project was for a non-profit architectural and public education organisation.

Cole (who has since moved to London and parted company with Burdocks) says that this first project was ‘the work I’m personally most proud of … we could directly see its benefit on real, everyday people. I continue to be driven to engage in human-centric design work, and ‘First Things First’ (particularly ‘FTF2000’) forms a large part of what has catalysed this line of enquiry for me.’

There are many reasons Peters feels ‘First Things First’ needs updating for 2014, but one development since 2000 stands above many others. As he states on his blog: ‘Given how much of our lives and work the Web touches, I believe it is critical that its presence and myriad implications should inform the next draft of the manifesto – not least because, as revelations over the past eight months have shown us (such as ‘The NSA files’ in The Guardian), the Web of today is not quite the Web we’ve always thought it was. Privacy, security and free speech on the web have never been more threatened, and I believe it’s important to acknowledge how this affects our industry.’ In conversation, Peters goes on to list other concerns about modern working practices: ‘There are other challenges in design and technology that have reached a fever pitch this year as well, including a critical lack of diversity in ethnicity, age and gender in our industries, and the insane (or, as we’ve seen in rare cases, fatal) work-life balance so many companies have been pushing for.’

‘First Things First 2014’ will undoubtedly get given a tough time from many quarters, just as the 2000 version did. In his 2001 book Obey The Giant, Rick Poynor reported: ‘Naive. Elitist. Arrogant. Hypocritical. Pompous. Outdated. Cynically exploitative. Flawed. Rigid. Unimaginative. Pathetic … These are just a few of the barbs and catcalls hurled at the 400 word text and its signatories by individuals who may have rejected its every line and sentiment, but apparently felt sufficiently rattled by its arrival to fire off a public response.’ Poynor went on to say: ‘In fifteen years as a design writer, I have never observed anything in the design press to compare with the scale, intensity and duration of international reaction to “First Things First”.’ And that was in the days before website comment sections promoted ‘open journalism’ and before social media.

When asked whether a possible backlash concerns him, Peters says: ‘I’m actually looking forward to whatever debates “First Things First 2014” will spark – both supportive and critical. The question of whether our work should be value-free or value-conscious is an important one to consider, especially as design has become a critical cog in the larger mechanism of technology, which in turn defines so much of our present-day cultural and social interactions. There needs to be an ongoing dialogue about the roles and values of our industries and professions in the world today. I expect part of that dialogue will be critical of the values “First Things First 2014” espouses, but that’s part of any debate.’

Criticality is at the heart of Peters rationale when questioning contemporary design practices; citing Rick Poynor’s essay ‘First Things First Revisited’ in Emigre no. 51 1999, Peters says: ‘Johanna Drucker suggested that what’s at stake in contemporary design “isn‘t so much the look or form … as the life and consciousness of the designer (and everybody else, for that matter),” which is a statement that could be equally applied to developers and creative technologists of all sorts. Drucker argued that we should always be asking “In whose interest and to what ends?” – given both the triumphs and tragedies of design and technology today, I’d suggest that [Drucker’s] question needs to be asked more often. It’s far too easy to turn a blind eye to the negative aspects of our industry, never mind those of our world at large. These blind eyes need to start turning into critical ones.’

Despite the amount of debate in the wake of ‘First Things First 2000’, I would argue that the graphic design profession has remained largely unchanged by the manifesto in the past fourteen years. Designers like Cole Peters, who were moved enough to create some change in their own practices, are rare. And maybe this, if nothing else, is a good enough reason for a ‘First Things First’ re-launch. What it will achieve in 2014 is yet to be seen, but Peters is adamant: ‘I believe we as designers have an inherent duty to be concerned about matters of ethics. Much of our work is intended for consumption at scale, which means that when we disregard our moral compass, the effects … have the potential to negatively impact a large amount of people. Any professional whose work has the power to influence people en masse has a duty to produce work that respects and honours those people.’

While non-designers may see the FTF manifesto as overly introspective and of no importance to them, I would proffer this thought to anyone outside the creative sector to consider. Imagine if other professions decided to initiate their own ‘First Things First’ manifesto – Members of Parliament, the banking industry, newspaper proprietors or payday loan vendors? If the design community can engage in open and public critical self-reflection, then why not other professions? Could action of this kind realign priorities for the benefit of all of society? Maybe it would, maybe it wouldn’t; but one thing is for sure, it wouldn’t look like navel-gazing – it would look like a healthy discourse on the nature of our contemporary society and the responsibilities we all have towards it. And for that reason I say all power to ‘First Things First 2014’. Where do I sign?

‘First Things First 2014’ will launch on Monday 3 March 2014. Follow the discussion on Twitter: @firstthings2014

‘First Things First Manifesto 2000’ spread in Eye no. 33 vol. 9, 1999. Design: Nick Bell.

Top: ‘First Things First’ manifesto, 1964. Design: Ken Garland.

Nigel Ball, designer and educator, Suffolk

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.