Spring 2014

Leftovers with a bad taste

In the past century the use of ‘trade characters’ built brand loyalty while reinforcing stereotypes

Uncle Ben’s rice is a beckoning house servant. Aunt Jemima’s pancake mix is the warm embrace of an antebellum mammy. We may not be what we eat, but marketing experts insist that we must have personal relationships with what we ingest. Ubiquitous commercial trade characters, the imagined embodiments of many nationally (now internationally) branded foods, humanise mass market products in the consumer’s mind.

Total loyalty to a brand through trade characters was essential to the success of competing national products. During the late nineteenth century, racial and ethnic stereotypes were routinely introduced as ‘friendly trade characters,’ invited into the homes and kitchens of harried housewives who benefitted from these ostensibly benign apparitions – a bit like religious iconography.

Racial exploitation was not the rule, but neither was it the exception. Trade characters were carefully devised to associate certain products with particular expectations. African American characters were maids, cooks, train porters and even children. Some were based on slaves, others minstrels, some depictions were remotely realistic others were monstrously caricatured – by today’s standards, all would be construed as denigrating the individuality inherent in any race of people. Yet all had a role to play in an ultra-stratified society.

The food industry would not build their brands on the foundation of anything too derogatory, but the threshold for acceptance was very different in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries than it is today. During the age of melting pot expansion, ethnicity and race were major themes in American life and humour throughout the popular culture outlets of the day. As trade characters, African Americans shared the stage with Native Americans (Indians), Jews, the Irish, Chinese, Italians, Mexicans, Germans (called ‘Dutch’ for Deutsch) and others. Food, however, had the largest wellspring of black and Indian trade characters; Italians came next at a distant third place (and only much later when Italian food was mass marketed).

Some products with these characters were harvested or processed by, or were indigenous to, the blacks and native Americans that represented them. Uncle Ben’s was actually produced by a black-owned company in Hilton Head, North Carolina. Native Americans were associated with corn (and all that was derived from it), as well as tobacco.

But the reasons for the adoption of most other trade characters were less noble. They blatantly reinforced the social and economic differences between the races on one hand and the pervasive racist sentiments of the nation on the other. The old canard about ‘knowing their place,’ is clear: their place is not in the dining room but in the kitchen.

These early trade characters were servants – or slaves. Indians were heathens or noble savages, but nonetheless exploited. Their collective images have morphed, altered or disappeared over the past 60 or 70 years, but they left scars on the victims of the image who accepted servitude or felt the pain of discrimination that the brands enabled.

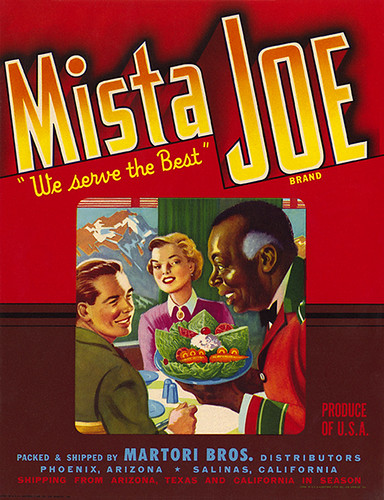

Mista Joe employs the Pullman porter, a middle-aged black man happily serving a young white couple.

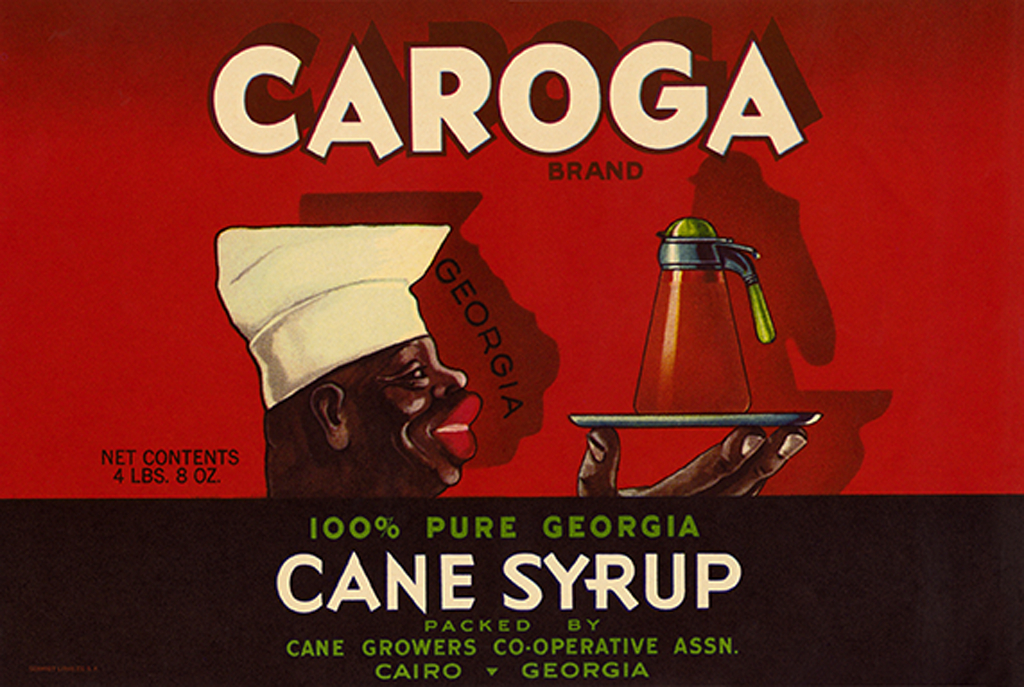

Top: Caroga from Georgia shows a black short-order cook, a common advertising trope in both the South and the North of the United States.

Steven Heller, design writer, New York

First published in Eye no. 87 vol. 22 2014

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 87 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.