Winter 2016

Olivier Kugler: bearing witness

This contemporary illustrator uses his ears and eyes – plus a camera, digital voice recorder, sketchbook, pencil, scanner and laptop – to document stories of exile, displacement and the complex reality of refugees’ lives

On a sunny afternoon in the autumn of 2016, illustrator Olivier Kugler travels to Birmingham in the UK to meet Wisam, a Syrian refugee with a young family. Wisam has a story to tell and Kugler is going to turn it into pictures. Over the past few years, Kugler has been interviewing refugees and others affected by the current crisis, drawing their pictures and telling their stories, which he will eventually turn into a book. Kugler meets Wisam and his children Mohamad (eleven) and Ranem (eight) at their new school, and then accompanies them back to their flat, where he also interviews Hadya, Wisam’s pregnant wife, taking more pictures.

He interviews Wisam via an interpreter, recording the conversation and taking photos. Wisam tells him about his former life as a businessman, his family, their departure from Damascus in Syria (after he had been shot in the legs at home), and their years of unhappy exile in the Egyptian port of Domyat. Then there were the nine days he spent on an overcrowded fishing boat (‘like battery chickens’) in the Mediterranean before being rescued by the Italian military. Then followed a lengthy cross-continental train journey from Sicily to the Calais ‘Jungle’ and a risky crossing to Dover. The family was reunited when they joined him in Birmingham.

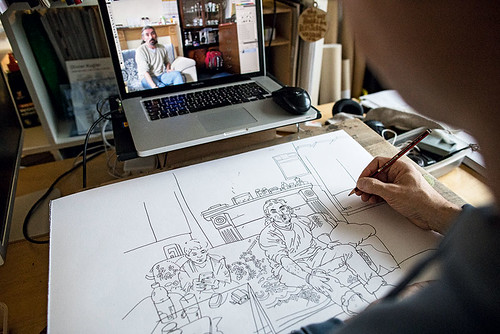

While he is with his subjects, Kugler rarely sketches; he is keen to note everything they say and do, to take in every detail of their faces, clothes and surroundings with his eyes and his camera. Later on, in the quiet of his studio, he will fill an A2 pad with pencil drawings of the encounter.

Photograph of Olivier Kugler by David Levene, 2016.

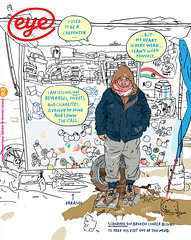

Top: Opening spread from ‘Escaping Wars and Waves: drawings by Olivier Kugler’ in Harper’s Magazine, February 2014.

Kugler is the contemporary face of reportage illustration, the art of going to a place where there’s a news story, looking hard, asking questions and coming back with the drawings. He grew up in Germany, but today is based in Dalston, East London. His illustrative style is subservient to rigorous research and inquiry. His work is recognisable through its distinctive line, made with an HB or B pencil, and the frequent inclusion of information and quotations from his subjects, and written commentary. Kugler encounters ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances and vice versa: he treats them all with a cool but empathetic eye. His planned book about the refugee crisis, which is likely to have the title Escaping Wars and Waves, is a time-consuming personal project, funded in part by a grant from Arts Council England.

Since Kugler settled in London in 2003, he has built up a strong body of editorial work. In 2012 Oxfam sent him to Burkina Faso to report on individuals affected by the food crisis in the Sahel. His interest in refugees was kindled in 2013 when Médecins Sans Frontières invited him to tell the stories of Syrian refugees in Iraqi Kurdistan, and later on the Greek island of Kos.

His book The Elephant Doctor in Laos was published in 2013 by Edition Moderne, a Swiss graphic novel publisher. Kugler also draws commercial illustrations for clients including Süddeutsche Zeitung, Reader’s Digest, The New York Times, The New Yorker, New York magazine and German GQ, to which he contributes a regular ‘how to’ cookery item. Other commissioned work often has a documentary element, such as his annual report for the New York organisation New Visions for Public Schools, or his brochure about the London headquarters of communications company Black Sun Plc. His cover for Rob Marr’s album Anatomy (2012) shows the singer-songwriter’s home studio environment with its deckchair, cat flap and cream and chrome Wurlitzer electric piano.

In more recent years, Kugler’s refugee reportage has been disseminated through events such as the Fumetto International Comix Festival in Lucerne, Switzerland, and through sympathetic publications such as Annabelle (Switzerland), Internazionale (Italy) and Harper’s Magazine (US), the long-established champion of reportage illustration. Kugler’s portraits of Syrian refugees for Harper’s was an ‘overall professional winner’ in the Association of Illustrators (AOI) World Illustration Awards, and exhibited at London’s Somerset House in the summer of 2016.

DRAWN FROM THE SCREEN

When Kugler has returned to his shared studio space in Dalston, East London, he makes drawings from his photographs on an A2 sketchpad. Kugler uses a strength ‘B’ Faber-Castell pencil, which he says enables him to draw fast without pushing too hard.

Words and pictures

When he carries out interviews, Kugler knows that the camera will pick up details and perspectives that would take too long to capture if he sat down and drew the scene. And in many cases, the people he talks to cannot spare the time to sit and pose; their story tumbles out before they have to move on. His digital photos are effectively ‘roughs’ from which he makes the next stage in the illustration: a black-and-white ‘B’ pencil drawing on a large sketchpad. These drawings are about four times bigger than their eventual size. Kugler rarely publishes any photos – they are effectively private ‘roughs’ – but occasionally he will stick photographic print-outs on to a rough layout that he sends to art directors to give them a clearer idea of how the finished design will look on a magazine page or spread. The next stage in Kugler’s process is to scan the drawing and then colour the image using the ancient computer program Freehand – to which he has a stubborn attachment – producing the effect of a saturated watercolour wash or gouache.

He adds handwritten notes that inhabit another layer of the file. This way, the English-language narrative can be replaced by other languages using a typeface based on Kugler’s pencilled handwriting made by Flo Gärtner of Magma in Karlsruhe (and a co-founder of the German type and design blog / magazine Slanted).

Kugler’s handwritten texts have become a crucial part of his distinctive approach to reportage, which has evolved slowly over time. His early work, made while studying in New York, contained short notes, but by the time of his Guardian slot ‘Kugler’s People’ in the mid-2000s, words had begun to fill every scrap of space.

By contrast, his more recent pictures about refugees contain fewer words and are better edited, making them more pointed and moving. When I suggest to Kugler that a valid criticism of his earlier work was that it had too many words, he replies: ‘I agree! When working on earlier pieces I was predominantly focused on creating good drawings. The editing of text and the placement of it in the layout played second fiddle.’

‘Un Thé en Iran’ (2009-10) was his first long sequential piece. Kugler had long admired the ‘slow journalism’ of French quarterly XXI, and was thrilled to receive a commission from Patrick de Saint-Exupéry, XXI’s editor-in-chief, asking him to do a 32-page story – fifteen spreads with a brief intro. For the assignment Kugler accompanied an Iranian truck driver, Massih, who was transporting bottled water across Iran, from Damavand to Kish Island. ‘I spent four days with him. Lovely guy.’ He had arranged to record an interview (through a translator), but the truck driver got cold feet at the last minute. ‘I didn’t want to do anything political,’ says Kugler, ‘just find out about his job.’ The resulting story contained fewer of the subject’s own words than Kugler had originally intended, but his disappointment was mitigated when ‘Un Thé en Iran’ was selected as the overall winner of the V&A Illustration Award in 2011.

His story for the Swiss magazine Reportagen no. 11 (June 2013) was an encounter with Luigi Bonaventura, a former Mafioso turned ‘supergrass’ who was in hiding in an apartment by the Adriatic. Here, Kugler’s pictures have a paranoid power that comes from their simplicity – with no colour and few words – and the banality of the situation: the apartment door with its strong hinges and multiple locks, a furniture unit against the wall and the single word ‘Berlusconi’ pointing to a portable TV screen. Kugler’s illustrations accompany a substantial profile by journalist Sandro Mattioli, who also appears in several illustrations, taking notes in a spiral-bound pad, or smoking with the Mafioso on the balcony with its distant view of the sea. Kugler was grimly amused to observe that Bonaventura’s son loved playing the video game Hitman.

When Kugler makes work for not-for-profit organisations such as Oxfam and MSF, the dynamic of the illustrator-client relationship evolves in interesting ways. ‘Olivier Kugler’s portraits give Syrian refugees a voice,’ says Andrea Kaufmann of MSF. ‘The drawings tell the stories of the portrayed people authentically and with dignity. It gives us the possibility to raise awareness of the circumstances in which the refugees live in Domiz and of the difficulties of their journey to Europe in a way that is different from when Médecins Sans Frontières speaks about the humanitarian situation we see during our medical aid.’ In the past MSF has worked with other artists and illustrators, such as Andrea Caprez and Christoph Schuler, whose work was published in the book Out of Somalia. The organisation has also worked with artists Anke Feuchtenberger, Stefano Ricci and François Olislaeger.

Kugler has produced two portfolios about Syrian refugees for Harper’s Magazine (‘Escaping Wars and Waves’ in February and ‘Waiting State’ in March 2014.) These features – sequences of single pages and spreads – are presented with no interruption apart from a short text intro. In the opening spread of ‘Escaping Wars and Waves’ (top), Kugler shows the impact of Syrian refugee influx on Kos: it is a human story, a diagram and a map. Kugler’s capitalised notes tell us that the Ferry Port is 150m away, that the Police Station (where refugees seek permission to continue their journey to Athens) is 50m in the other direction. On the distant surface of the sea there are black marks identified as float rings, inner tubes from cars; by the seafront there are oleander blossoms. Hanging on a big tree in the foreground, which Kugler makes transparent in order to show the scene in full, he draws jeans and underpants hanging out to dry. To the left we see that ‘Claudia’s got to move’. Kugler writes: ‘For the past seven years she has been selling souvenirs here, mainly sponges, to tourists. Because of the refugees, though, the tourists stay away.’ A giant crane is lifting Claudia’s stall so that it can be relocated.

Harper’s Magazine art director Stacey Clarkson James worked on the Syrian portfolios and speaks warmly about Kugler: ‘At Harper’s, we value long-form journalism and a distinctive voice in a writer or artist. Olivier has a very strong instinct for stories that will resonate over time and deep compassion. He foregrounds the voices of the refugees as they elucidate their experiences of escape and survival in an empathetic and moving way.’

In a page about Rezan, a fashion designer, Kugler brings a single character into sharp focus. The reader’s sympathies are immediately engaged by the portrayal – the face in half profile dominates the page’s centre – and the sincerity of the quoted speech. Rezan states: ‘The Islamic State had blown up all the trees in an orchard that belonged to our next-door neighbour. I used to play there when I was a child. I helped out during the summer. You can rebuild a house easily, but the trees? It took a lot of time and care for them to grow and prosper.’

Kugler adds another layer of engagement in the details he chooses to show – the smartphone on charge, the Converse and Disney T-shirts, the little set of watercolour paints and brushes. In the note describing Rocca, the eight-year-old niece sitting on Rezan’s lap, he adds: ‘Her uncle was holding her like he is holding her right now. He was hugging her all the time.’

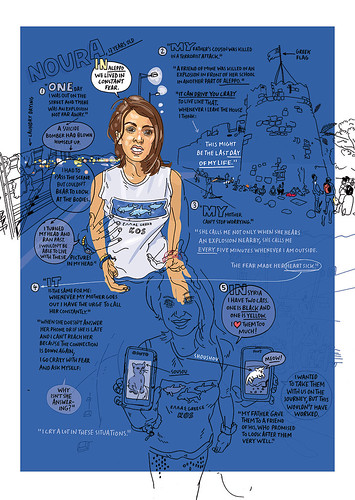

A TEENAGER FROM ALEPPO

One of the portfolio of drawings that Kugler made for ‘Escaping Wars and Waves’ in Harper’s Magazine, February 2014. In addition to the spread featured at the top of this article, Kugler focused his attention on four individual refugees: Sherine, a physiotherapist; fashion designer Rezan; Omar, a medical student; and teenager Noura, shown right.

Early years in Europe and the US

Kugler, who grew up in Simmozheim, a small village by the Black Forest, Germany, first became interested in drawing and telling stories through pictures when he discovered Hergé’s Tintin stories at the age of eight. His father Klaus Kugler, a prolific artist, urged him to learn to draw through observation, and told him he should draw from nature – flowers, hands, faces – and go to life-drawing classes. After military service in the Navy, the young Kugler took a foundation course in drawing and painting in Stuttgart. However, he soon found there was no illustration degree available to him, and he studied visual communication for a degree at the Fachhochschule für Gestaltung in Pforzheim (southwest Germany) for five years. During that time he went to Athens, Georgia, as part of an eye-opening exchange semester in 1995 with the University of Georgia in the United States. While he was there, his teacher Alex Murawski recommended that he look at the work of narrative artist Alan E. Cober (1935-98), known for his illustrations for The New York Times, Rolling Stone and other publications. Cober’s drawings made in nursing homes and mental institutions made a huge impression on Kugler.

His final diploma project in 1997 was a piece of visual reportage about the Reeperbahn in the St Pauli district of Hamburg. Titled St Pauli wider den Strich [St Pauli against the grain], the French-fold, casebound book he made mixes longer texts, snapshots, portraits, thumbnails and full page and double-page drawings in which he casts his unblinking eye on cafes, souvenir shops, porno cinemas, strip clubs, music venues and the Salvation Army. He focuses on individual stories such as Erwin Ross, the late painter (known as the Rubens of the Reeperbahn), tattooist Ernst-Günter Götz, Rosi’s Drei Hufeisen Bar and Störtebeker. Since it was a graphic design course, Kugler’s final project integrated typography, photography and collage as well as monochrome pencil drawings, which hint at his mature style, though there are few handwritten words other than in the signs and the occasional label. At the time he did a few drawings in pen and ink, but one day he ruined a drawing by knocking over the inkpot. He has stuck to pencil ever since.

After university, Kugler worked for nearly three years as a graphic designer, mainly doing catalogues and other routine work at Das Dialog, the Karlsruhe agency now known as Hedgehog. When his application for a scholarship (from the German Academic Exchange Service) to do an MFA in illustration at the SVA (School of Visual Arts) in New York was successful, he grabbed the opportunity with relish. He had just turned 30, and the experience crystallised his determination to work as an illustrator, studying with strong personalities such as illustrators Marshall Arisman (who led the MA course), Carol Fabricatore and Mirko Ilić. Kugler says: ‘Fabricatore was the main reason why I chose SVA to do my master’s degree. When I first saw her amazing work online I told myself “This is what I want to do!” She is a graduate of the SVA’s Illustration as Visual Essay programme that she later taught on.’ Fabricatore was taught by Robert Weaver at the SVA, and Kugler notes that ‘her work and teaching is inspired by Robert Weaver’s approach to drawing on location.’

He also took creative writing classes at SVA, which he didn’t enjoy. ‘I just wanted to go out and draw! But in the end these classes might have been responsible for me starting to add quotes into my drawings from conversations I overheard when drawing on location.’

New York was full of terrific subject matter. Kugler stumbled upon Alberto, a homeless Puerto Rican man who was living in car wrecks abandoned in a parking lot in Spanish Harlem, scratching a living by selling stuff he found in other people’s trash. When Kugler started scribbling Alberto’s quotes around the sketches, he realised that he had found his own style of working. The result is gritty, moving and vivid, using some graphic novel techniques in a documentary context. It is often funny, too: throughout the visual sequence there is a speech bubble with the pop song hook ‘Hey Macarena’, which in the final frame is revealed to be a singing toy monkey. ‘Shut up stupid monkey,’ says Alberto. ‘I am not surprised you ended in the trash.’ Some of his SVA drawings came to the attention of New York magazine, resulting in his first editorial illustration assignment, Steve Fishman’s ‘I Want to Be a Millionaire’ (2001), in which Fishman tries to get a hip-hop karaoke business off the ground.

On his return to Europe, Kugler found a champion in art director Roger Browning at the Guardian. Browning commissioned him for a variety of assignments, including a trip to the Hay literature festival in 2003, a feature about different people’s New Year resolutions, and a portrait of novelist Jonathan Franzen.

Browning recalls: ‘He emailed both Maggie Murphy [another Guardian designer] and me, and we immediately loved his work … I could see he had potential immediately. Maggie and I “raced” to be the first to commission him.’

The portrait of Franzen was not typical in that Kugler had to work entirely from a photograph, though he added a touch of authenticity by including drawings of Alberto’s streetscape as a background, complete with archetypal New York City water towers. The picture, used on the cover of the Guardian Review section, went on to win Kugler an AOI illustration award in 2004.

In the following years, the Guardian’s Richard Turley commissioned him to draw ‘Kugler’s People’ for the paper’s G2 supplement. His subjects included a ‘Fruit & Veg Guy’, a Croydon fish & chip shop proprietor, a Kilburn GP and a black, Jamaican-born farmer in Cornwall.

An idiosyncratic detail that distinguishes Kugler’s work from other reportage illustrators is the inclusion of multiple marks for the subject’s movements as they shift position, turn the other way or gesture differently with their hands. Kugler’s reasoning for this is simple: ‘I only draw what I see. That’s why I want to start again when the subject moves!’

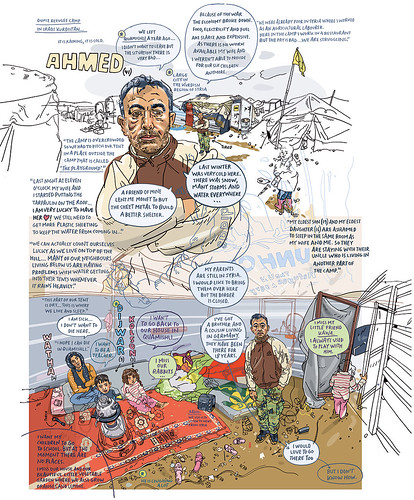

ORDINARY PEOPLE

Olivier Kugler’s drawings show people in Domiz, a camp in the Dohuk governorate of Iraqi Kurdistan, where more than 42,000 Syrian Kurds have sought refuge from the Syrian civil war.

Ahmed and Watha battle with the problems of keeping their tent dry. Hamed is an employee at Issa’s barber shop, one of several small businesses opened by refugees in Domiz to provide basic services.

Escaping wars and waves

Kugler’s main preoccupation at present is to document the stories of Syrian refugees in the format of a full length book. The Arts Council of England have given him a small grant to continue the work that began as assignments for MSF in Domiz (Iraqi Kurdistan) and in Kos. The book is tentatively named Escaping Wars and Waves, a title he used for one of the Harper’s pieces.

‘In April I spent time with young Syrian men in the Calais “Jungle” camp trying their luck to cross the Channel,’ said Kugler. Since then he has met other Syrians in the UK: an anaesthetist who now works as a nurse; a young man fleeing conscription whose first sight of England was a motorway car park in Kent when he jumped out of the back of a truck; and an activist who co-organised a 100,000-strong march through London.

Kugler believes that the stories of refugees affect the whole world, with ramifications that will be felt for decades to come: ‘My challenge is to distil as many of the stories as possible into a cogent and compelling narrative that will affect the reader in the way my experiences of meeting these people has affected me,’ he says.

He plans to interview and draw people who are not refugees, but who have nevertheless been affected by the crisis: an Iraqi Kurdish psychotherapist; a British expat; business owners affected negatively by the influx of new people; and a volunteer schoolteacher organising prams and wheelchairs for refugees forced to leave such items behind. He hopes to interview former labour MP Alf Dubs, born in Prague in 1934, who was one of the Jewish children who came to the UK via the Kindertransport.

Kugler’s own father, Klaus, was born in Südmähren, Southern Moravia, in a village (Vlasatice, formerly called Wostitz) now in the south east of the Czech Republic near the border with Austria and Slovakia. He was three years old when the family had to flee at the end of the Second World War. ‘My father was a refugee,’ notes Kugler.

The forthcoming book will provide Kugler with an opportunity to free himself from the expressive constraints and financial challenges of working as an illustrator for hire, waiting for assignments that come in fits and starts. The new book is a bid for both independence and autonomy. ‘Spending more time and focusing more on the storytelling aspect will take my work to the next level.’ The book will allow him to experiment with layouts: ‘There might be spreads with drawings including a lot or hardly any text … there might be pages only showing drawings and no text … and there might be pages with no drawings at all and only text … let’s see!’

John L. Walters, editor of Eye, London

A ‘SUPERGRASS’ IN HIDING

Illustration for the magazine Reportagen, which shows writer Sandro Mattioli smoking with Mafia informant Luigi Bonaventura on the balcony of the latter’s apartment, with its view of the Adriatic Sea. The article can be seen online: reportagen.com/content/mafioso-ausser-dienst.

---

SIDEBAR: The reporter as ‘special artist’

While the tradition of drawn, visual reportage goes back centuries, the use of specially commissioned illustrators became widespread with the rise of reasonably economical and well printed illustrated magazines in the mid-nineteenth century. The emerging pictorial journalism of papers such as the Illustrated London News, Illustrierte Zeitung, L’Illustration and Harper’s Weekly covered both domestic and foreign news, from petty crime and gossip to war and revolution. These ‘Special Artists’, as described by Paul Hogarth in The Artist as Reporter (1967), had to ‘have the intuition of a journalist for knowing what to draw; and also to know by instinct or design when to be where …’

Artists working in this way included Arthur Boyd Houghton, Frank Vizetelly, and Alfred Waud. As photography began to usurp the purely pictorial role of the special artists late in the nineteenth century, reportage evolved. Artists as different as Otto Dix, George Grosz, C. R. W. Nevinson and Paul Nash cast their gaze on the new century’s follies. Many illustrators documented the Second World War, including painters Eric Ravilious (who died while working as a war artist in 1942) and Edward Ardizzone (see ‘Ardizzone at peace and in conflict’ in Eye 93). Feliks Topolski covered the Russian Front and Edgar Ainsworth reported on the liberation of Belsen. Ronald Searle’s clandestine drawings of the Japanese labour camps, in which he was incarcerated for four years, were painfully vivid.

One of Searle’s books, made in collaboration with his then wife Kaye Webb, is an interesting antecedent to Kugler’s project; Refugees 1960: A Report in Words and Drawings is a frequently harrowing yet humane account of the refugee crisis of that time. Also in the postwar period, picture magazines as varied as Fortune, Punch, Sports Illustrated and Holiday had sufficient budgets to send illustrators on editorial assignments, as did the burgeoning newspaper magazine supplements.

Artists such as Robert Weaver, Gerald Scarfe, Ralph Steadman, Paul Hogarth and Paul Cox brought style and invention to all manner of subjects, serious and light. Recent years have seen remarkable personal odysseys by illustrators Joe Sacco and Emmanuel Guibert (see ‘Framing the evidence of war’ in Eye 73).

Olivier Kugler is full of praise for Lucinda Rogers (see Eye 91) – whom he describes as ‘the ultimate on location draughts(wo)man’ – but he places his own work more within the tradition of French and Belgian bandes dessinées. Kugler admires Joe Sacco’s ability to collect material for a story that he then makes into sequential drawings (including a cartoonish version of himself), but notes that Sacco ‘is a proper journalist, a journalist by trade. When he goes out into the field he does so in order to collect material to tell a story and he knows how to do so. For me it was more that I want to go out and collect material in order to create a series of great drawings.’

John L. Walters, editor of Eye, London

First published in Eye no. 93 vol. 24, 2017

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 93 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.