Spring 2000

Reputations: Makoto Saito

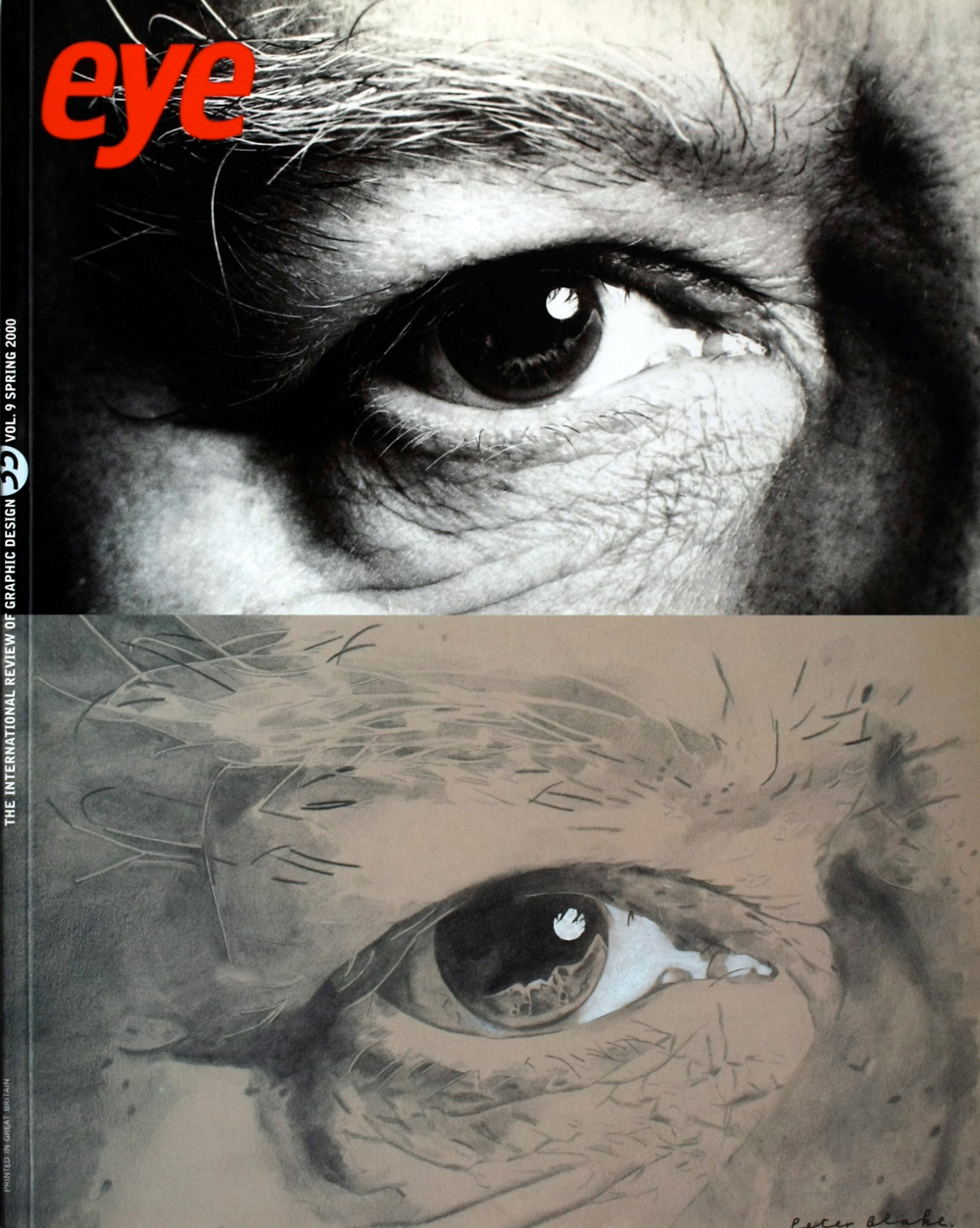

‘I don’t trust words. You can say anything with words. I prefer a visual means of communication allows the message to be more direct’

Makoto Saito has worked as a commercial art director, creative director, product designer and film-maker, as well as a graphic designer, but he uses the poster as his signature medium. His experimental and provocative images challenge every expectation of the format and have made him one of the most important and influential figures in poster design of the past twenty years.

Saito was born in Fukuoka, Japan in 1952, and discovered his talent for drawing and painting early in elementary school. He attended Kokura Technical High School and soon after graduation, without any further formal art education, began his career in visual arts as a printmaker. His early prints were exhibited internationally, and are represented in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In 1974, Saito joined the Nippon Design Center, a house agency for major corporations co-founded in 1960 by Ikko Tanaka in Tokyo. During this time he focused his energies on commercial work, his interest in poster design being prompted by a desire to reach a wider audience than that for fine art prints.

In 1982, at the age of 30, he launched his own firm, Makoto Saito Design Office Inc. The posters he has since produced for clients such as the clothing manufacturers Ba-Tsu and Alpha Cubic, for Virgin Japan and the Hasegawa Company, re-interpret the poster’s role. Saito’s designs are almost entirely devoid of text, the company name often emerging from the imagery almost as an afterthought. Rather than selling a specific product, the posters convey a sense of the character of the company, or seek to provoke a reaction to it.

Saito rejects computer technology, though his hand-worked designs may be subsequently recreated by an assistant in the computer environment. The finished prints, on thick, high-quality paper, meticulously printed in dense layers of ink, blur the distinction between promotional medium and fine art print. His posters are included in the collections of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the New York Museum of Modern Art, the Design Museum, London, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and many others.

Saito’s work has won many awards worldwide, including a number of honours from the Art Directors’ Clubs of both Tokyo and New York. His most recent exhibition, a 100-poster retrospective entitled: ‘Makoto Saito: The Art of the Poster’, opened last November at the Massachusetts College of Art, Boston, and was curated by MassArt Professors Elizabeth Resnick and Jan Kubasiewicz, who conducted this interview with the assistance of June Tanaka, a translator.

Jan Kubasiewicz and Elizabeth Resnick: What does it mean to be a poster designer, as opposed to a graphic designer in other areas?

Makoto Saito: I am a poster designer, but I have always been unhappy about the way posters are treated: once they have served their purpose they are discarded. I devote a lot of time and effort to making posters. I take full responsibility – from choosing the paper to the very end of the production process. That is important to me. Since I am using valuable paper and natural resources I cannot bear the idea that the poster will then be thrown away after use. I want my poster to be one that someone will steal and keep, that will be treasured and really enjoyed after it has fulfilled its initial function.

You want your posters to be kept as works of art. What do your clients want from them?

The first question I ask a client is: “What do you want to achieve? What do you want the poster to do?” I ask because people have different expectations and look at things in different ways. So someone may ask, “Will this sell my product?” while someone else will say, “What on earth is this?” Someone else may say: “It’s beautiful. I’d like to buy one to keep.” To give you an example: in 1994, the fashion company Ba-Tsu was not doing well – the company’s sales were declining. The owner of the company is a well known poster collector and has a huge collection. He loves posters. I suggested that we should create something he would really love. This had nothing to do with marketing strategy. As a result, the company business picked up. The head of the company recovered his vitality, and this in turn stimulated the people around him.

Ba-Tsu designs and sells clothes all over the country but it is based in Harajuku, the district where more young people – particularly young teenagers – hang out than anywhere else in Tokyo. I wanted to capture the energy of those kids wandering about the area, looking for something, wanting something. I tried to get across my idea of Harajuku as a town of young people by making a montage of those young people and using each letter as something akin to a person’s character. The poster consists of three pieces to be displayed side by side like a triptych. In addition, each piece is designed to be appreciated as a separate work.

What happens when the expectations of the client are radically different to yours?

I am a professional artist. No matter how much the client is willing to pay, I will not accept a job I do not agree with. However, I am also a good salesman. I can sell things very well, including myself. Not only do I sell myself, I sell whatever my clients want me to sell. That’s what I do for them. Companies I have worked for, like Juno or Umword, have really improved their business over the past twenty years. Some firms have even reached a turnover of 4 billion yen and I helped them do this.

In fact, more than half my income comes from being a consultant on marketing strategy to various companies. Some people (particularly those from overseas) view me solely as an artist, but that’s not the whole truth.

How does a poster differ from a limited edition fine art print?

You can put your energy and sensitivity into each copy of a poster by limiting the edition. And each copy lives on even after it has finished its task of advertising. This dual character of the poster, being at the same time a work of art and a medium of communication, is what I am aiming for. However, I have nothing against mass produced posters. If a limited edition poster is not appropriate, if a mass produced poster will serve the purpose better, I still get creative satisfaction from it. I just take a different approach to it.

Most large Japanese corporations do not understand this difference. Their main motive is to make money and to increase their sales. I am willing to work with them and provide my skills as an art director, but I have no intention of really giving myself as an artist. I do not intend to

devote my efforts as an artist to people who neither understand nor appreciate art. If they prefer me to work as an art director, then that is what I will do. It is easier for me. And I can charge them a fortune!

Posters usually include both images and words. How does this split between the non-verbal and the verbal function in your work?

I don’t trust words. You can say anything with words. Before man could speak, nobody lied. You couldn’t hide when there were no words; you couldn’t lie or disguise anything. With words you can say nice things but, perhaps deep inside, it could all be just a bunch of lies. In the very beginning, when I started working, I made it a general rule not to use words.

What is more, when you try to express something in Japanese, you are faced with the extremely delicate nuances of the language and often end up with ambiguity. So I trust more in the power of the visual. I prefer a visual means of communication because it allows the message to be more direct. I also have in mind people outside Japan so I don’t like to rely too heavily on the Japanese language. I would rather conceal this aspect of myself and leave people to react to the work on its own. I guess that I don’t want people to prejudge my work according to my nationality before they have really seen the work itself. I think I started this fad for the text-free poster. When ten people look at a poster of mine, they will imagine ten different things. If a hundred people see it, there could be up to a hundred different interpretations.

When did you realise you wanted to be an artist?

In elementary school.

Did you draw at school?

Yes, and I still do. But since school I have not read a single book. I don’t like Japanese writing. I’m not suggesting this is a good thing. I don’t have the same problem with English. Even if I don’t understand the meaning of the words, I am aware that English feels right to me. When I read Japanese, I have to try to follow the meaning. I’m a feeling person. I like to feel things; I don’t want to be influenced by anything. When you read a book, of course you are affected by it – you think, “Maybe that’s right” or “That’s one way to think about it”. If I don’t read books, I can stay pure, for better or worse. I want to remain myself.

What was your early art training?

I have no formal art training. I started out as a printmaker, but I became discouraged. I had a few teachers who helped me, but they didn’t teach me the actual techniques of printmaking. So I found out about printmaking by trying each technique for myself. I am different from other people, and that difference is the source of what I am doing now.

The Japanese fine art world is very cold and insular, so I switched to commercial art. I thought it would be more interesting to keep putting work in front of the public. The reaction I got to my commercial work when it appeared in print on the street was far more immediate than the response to the prints and paintings that appeared in private exhibitions. I realised how much I enjoyed the instant response one gets from working in design. I probably moved across to commercial media as a means of creative expression, despite my attachment to painting, because of the satisfaction I got from an audience response to my work.

Did you go to university?

No, no, no, no – although I sometimes teach at universities now. If you think you can benefit from a college education you should go to college. I believe that in order to improve yourself you have got to learn to choose the life that suits you best. You can rely upon nobody but yourself. Knowing yourself is more important for getting started in life than studying and gathering other kinds of knowledge.

Who were your early influences?

There are not many people I can think of who influenced me. There were people whom I admired, like Stanley Kubrick, my favourite movie director. Especially in his film A Clockwork Orange. I liked the visuals, the colours – the way you physically feel what is happening on screen.

Who inspires you now?

There are people whom I admire, though they did not influence me: Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein in the 1960s, Cy Twombly, and Philip Guston. In design I admire the Stenberg Brothers, the Russian avant-garde. Their work is very strong. They are really the only people who have forcibly impressed me as a designer. The others I don’t think much of.

Another specific influence that I am aware of, I guess, is my children. You can probably see it in the drawings for Ba-Tsu (1998). My children have renewed my sense of the pleasure and satisfaction to be had from doing things by hand. The work comes from that.

How do you express your ideas in a poster? Which elements come first?

Imagination comes first. When I am creating an image, questions arise. Should it be a photograph? Should it be hand-made? My decision is based on how far I can visualise the finished product. If I can imagine the whole thing, from beginning to end, it’s not interesting, it doesn’t really turn me on. But if there’s the potential of something that’s still not visible, still not clear, then that’s something I can look forward to. The more uncertainty there is in the process, the more I look forward to seeing the final product.

Apart from posters what other kinds of media do you work in?

I’ve been a film director: Makoto’s Story, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 was shown on national television over five days several years ago. It won the Grand Prix at a competition in Montreal. Each story was about ten minutes, filmed in black and white and surreal in style. At the moment I’m into sculptures and murals. I also do planning, directing, editing and so on for commercials.

Do you still paint pictures?

Yes. Some of my prints are in the MOMA collection, and others have been bought by galleries. Yet I find design more interesting.

What do you feel about digital media?

This whole area is like a flowing river. It is almost like information itself. But there is no feeling conveyed in the media today. I’m not like a flowing river. I am on the bank, walking with my own two feet at my own pace and that, to me, is how it should be. When something suddenly inspires me, or an idea suddenly hits me, my body disappears and I’m like the river itself, flowing very fast. I am instantly faster than the river. Time disappears. I am suddenly transported to another place. No matter how fast a computer can work, my imagination is much faster.

The computer is just a tool. You can go anywhere you want inside your mind. People who work with computers are all using the same tool. It is as though they are all using the same pair of hands. Technically they are very skilled people, and they are good at what they do. But no individual personality comes through in their work. That is why I find it boring.

Let’s say I draw a line by hand. If it is produced by a computer, of course it’s a straight line, it’s a perfect straight line but it is dead. It is different from a hand-drawn line. The perfect line drawn by the computer is not attractive because it is too perfect. Anything that is totally perfect is not attractive or appealing at all. When there is a flaw, a mistake or something is not perfect, that is where individuality can show through. When an object is too perfect, or a person is too perfect, I don’t find them interesting.

The appreciation of imperfection seems quintessentially Japanese. How does this operate in your design process?

I aim at perfection, but naturally I fail. The issue is the degree of failure, the degree of incompleteness. If you look at the finished work as a whole, it is strongly affected by this element of imperfection. Then it’s a matter of whether this is good or bad. I follow my instincts or my senses or my imagination. I go with what my body feels.

How do you know when a work is complete?

I feel it’s perfect. That “that’s it”. Then, let’s say, in the process of photographing the artwork, I realise that there is a mistake. Of course it is too late; it’s going to be too much of a hassle to redo it, and it’s going to cost tens of thousands of dollars so I can’t change it. I have to work with what I have. Sometimes I spot some mistake that I have made at the last moment. That really upsets me, but at the same time that is what is so interesting.

But sometimes I question whether having everything turning out exactly as planned is always good for the final result. I wonder

whether it might not be better to introduce mistakes of this kind.

Has something accidental ever triggered this sense of ‘that’s it’?

It happens all the time, to a certain degree. In a sense, I go into each job knowing only vaguely what I am going to do. I look around and try to do whatever is possible to come up with the best possible work. So, maybe it will fail, maybe it won’t. But that’s how I actually start the process. I don’t do presentations to my clients. I don’t show the work until the very end, until it is done.

How many people work in your studio?

There are three other assistant designers. Basically I do everything and they help. There is also a management person.

What is your design process?

MS: When a project comes into the studio I come up with a rough idea. I take bits and pieces and cut things up while an assistant stands by to bring me supplies. When I have a rough image I ask the assistant to leave and I work on my own. Once the image is fixed, I have an assistant save it on the computer. I don’t operate computers myself. I give directions to my assistants and they work on the computers.

You enjoy an international reputation as a poster designer. How does that affect your role in the Japanese design community?

I am a member of the Tokyo Art Director’s Club. Of the 70 members of this group, perhaps three or four really know what they are doing. The rest are good guys, but they don’t know what they are doing. Whatever is decided by majority vote tends to be mediocre. Because I am so outspoken my work has to be maybe ten times better than that of other ADC members in order to win. It tends to get very political.

Will the poster as a medium survive in the twenty-first century?

It will survive, though not necessarily as we know it. Posters have existed in the past as sources of information, but the way information is conveyed has changed over the years. From a designer’s perspective, the poster seems important as a tool of communication. However, if society no longer has a use for it, the poster as a medium will decline. But I am confident that no matter what, my posters won’t disappear.

What do you see yourself doing in the future?

I really don’t know if I am going to continue my life as a designer. I might suddenly move in a totally different direction.

My ultimate ambition is to choose seven major cities of the world, perhaps including London, Paris, Tokyo and New York, and send my own personal message to them simultaneously. I would buy up all news and advertising media in the cities for a period of three weeks to a month. Each city would then wake up one morning to billboards, newspapers and so on displaying my message.

I think it is possible to do, so I am trying to find the money for it. Designers usually look for some kind of meaning. I want people to remember me as this outrageous designer who did this mad thing. I am determined to go through with this plan within the next three to five years.

What would the message be?

I cannot say yet. At the moment it is just a vague idea, I haven’t fully decided. I want to do something where I won’t have to think about clients at all, where I can do whatever I want to do. I will be my own client.

How would you advise a student wanting to become a successful designer?

I would ask: do you have a “weapon”? If so, what is it? If you have a weapon, you will be fine, you’ll be ok, but if you are empty-handed you won’t get anywhere. This is really fundamental. I think this is the key.

The same is true for design or painting, architecture or business: it is a question of whether or not you have a weapon. It is something you are born with and it is what you are going to fight with.

So what do you consider to be your weapon?

I know how to confound and exceed the expectations of the viewer. I think this ability to achieve something unexpected is my weapon, my advantage over others.

Jan Kubasiewicz, design historian, MassArt, Boston

Elizabeth Resnick, designer and teacher, MassArt, Boston

First published in Eye no. 35 vol. 9, 2000.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.