Spring 2019

States of independence

The fragmentation of the type market has led to new ways of examining, acquiring and enjoying typefaces … and some confusion

The type world has seen some remarkable changes these past few years. Web fonts (since 2010), colour fonts and variable fonts (2016) have all been promoted and embraced as the most likely and likeable candidates to cause the next typographic paradigm shift. However, what is arguably the most dramatic change in type is not a technical innovation, it is a fragmentation of the market itself, leading to new ways of examining, acquiring and enjoying typefaces, and possibly quite a bit of confusion among groups of users.

A couple of decades ago, the font retail market was clearly set out and most type users had their favourite one-stop shopping platform. Each of the major type shops had its characteristics – innovative, designer-oriented, corporate, maverick or geek boutique – and most users felt at home in one of these places. At the time, the business of getting the font to the customer was shifting: from the data storage media that had ruled 1990s desktop design to the web download. Fonts had a big advantage over other digital products. The files were tiny and easily downloadable – even when bandwidth issues still played a major role. Yet despite the minuteness of their files, they were seen by most users as a painstakingly crafted tool with an aura of quality and necessity.

In the late 1990s it was not always an obvious step for a young type designer to get on board at an international distributor. There were selection processes, waiting times and stern judgements on the originality, usability and marketability of a new typeface family. The advent of MyFonts was instrumental in changing that. In the 2000s this platform, created by digital pioneer Bitstream, steadily became the world’s largest for buying licences and downloading fonts. The platform was part of a new kind of democratisation on two levels: its open door and ‘level playing field’ principle meant that emerging foundries had access to customers; and many non-specialists developed a growing interest in type, helped by a foolproof font-finding system and a nifty type recognition script with the naughty name WTF (What The Font).

Space Mono released by Colophon Foundry. Design: Anthony Sheret, Edd Harrington, Benjamin Critton, 2016. Top: Beatrice, released by Sharp Type. Design: Lucas Sharp, Connor Davenport, Kia Tasbihgou, 2018.

Lone wolves

There were always digital foundries that opted for the lone-wolf position, deciding to reach out to advertising and graphic design studios without help from distributors. A few independent foundries in the US (such as Hoefler & Co. and Sharp Type) and quite a bunch in Switzerland, the Netherlands and the UK, developed a personal market of discerning users. But most foundries relied, at least in part, on distribution. They built their own balanced network of online distributors.

As Sarah Snaith’s article in this issue clearly points out, all of this is now shifting. More and more medium-sized foundries tend to rely less on their once-trusted distribution networks and are venturing out on their own, coming up with special features that can turn their shops into amazing boutiques, or even virtual pubs or bars where kindred spirits drop by to hang out. Each foundry aims to create a stable market of regulars who actually buy when dropping in. Some are almost there. There are also various new alternative platforms with innovative and smart concepts, proposing a new take on what FontFont and Emigre did in the early 1990s: bridge the gap between innovative type designers and their possible audience and market. Right now, the number of places where fonts can be seen, examined and acquired is multiplying, exploding, fragmenting. Some are briefly introduced below.

Drawing on the company’s rich graphic design history, IBM Plex is a typeface whose characters serve ‘as a medium between mankind and machine’.

How did this shift come about? Factor one: enthusiastic production. Worldwide, academia’s output of talented, highly skilled type designers is growing. For years, the masters courses in Reading, UK, and The Hague, Netherlands, were the places to go to for a degree in type design, but over the past decade similar programmes have opened in Latin America, the US and across Europe. Dozens of talented graduates join the type community each year. About half of them end up working at a type studio (often specialising in corporate and institutional assignments), while the rest hope to find a platform to launch their own type families and their own microfoundry. Happily, several new initiatives make such efforts less cumbersome and more fun.

Factor two: the power of free fonts and subscriptions. Google Fonts, launched in 2010, is an open-source library that has developed from a set of beginner’s fonts with limitations into an admirable multi-script collection. It has always been presented, somewhat idealistically, as a way to improve web typography and allow new type-users to explore fonts and font families. The Google team also offered type designers increasingly handsome one-off fees for the royalty-free, open-source families they wished to acquire from them, allowing the designers to develop and sell expanded versions of these families. The ubiquity of Google Fonts is staggering, with (according to Wikipedia) more than 17 trillion fonts served; this means that each of its 877 fonts has been downloaded more than 19 billion times [in late 2017], which means that each person on Earth has, on average, downloaded each font at least two or three times.

IBM Plex released by IBM. Design: Mike Abbink and Bold Monday, 2017-18.

One-stop shopping

Some things about this library are wonderful, but some are troubling to the type world. Typefaces that were designed as near imitations of popular faces are now more famous and loved than the historic originals. Another problem is that Google Fonts, being free, has twisted people’s notions of what a typeface is worth. It is the first (and only) stop for many web designers working with small or non-existent budgets – good in some situations, but damaging in others. It has also become a huge, free asset for million-dollar companies offering online design services, such as Wix or Canva.

Design software companies, not quite the size of Google, have also developed various ways of making money from fonts by not charging for them. Twenty years ago, Adobe added CDs with impressive collections of fonts (mostly their own) to expensive software such as Photoshop. Their Typekit service – acquired in 2011, rebranded Adobe Fonts last year – now offers ‘free’ fonts to subscribers to their Creative Cloud software collection. In a way, typefaces are back to where they were in the times of huge typesetting machines: not so much machine parts as typographic ‘bricks’ that come free of charge with the software to design the ‘buildings’.

Factor three: possibly the biggest series of changes that shook a generation of type designers into a more critical, individual and entrepreneurial mode must have been the Monotype acquisition rush. Between 2006 and 2014, the company (owned since 2004 by a Massachusetts private equity investment firm) absorbed its three main competitors: Linotype, MyFonts, and FontShop. Each of these companies confidently accepted the challenge, convinced that their own identity would remain intact under the listed corporation.

IBM Plex released by IBM. Design: Mike Abbink and Bold Monday, 2017-18.

The most dramatic change was in Berlin, where FontShop had been revered as a pioneering typeface retailer and foundry for three decades, as well as for its world-renowned annual conferences. I expressed some unease about Monotype’s plans when reviewing last year’s TYPO Labs tech conference on the Eye blog: ‘I hope … that Monotype’s generosity in financing (with the support of Google) and organising (with admirable precision) a conference that gives their competitors additional power and incentives to collaborate, unite, or challenge the establishment, is genuine and long-lasting.’

Flash ahead to summer 2018. Shortly after TYPO Berlin (May), Monotype announced that the expected 2019 event would not take place. Within weeks it became clear that all conferences (except ‘branding-focused’ one-day events) were cancelled. As part of an ‘efficiency’ programme, the company fired the entire conference team, as well as the font production team. FontShop is no longer mentioned in Monotype’s list of brands.

Back to retail. Monotype has focused on MyFonts as their primary online shop, gradually modifying the platform’s informal communication into something more corporate, with growing attention to Monotype’s own products. At the same time, efforts have been made to add as many new foundries as possible. Monotype seems determined to be the place that literally has everything – offering a typographic version of the ‘long tail’ marketing model, in which a handful of bestsellers form a narrow, steep spike on the sales chart, and the myriad products that sell less, down to almost nothing in a long, long near-horizontal curve (the ‘tail’), still make the company little bits of money at each sale.

As more and more talented designers have chosen type design as their preferred means of expression, the time has come for independent designers to grab the wheel again. One of the first initiatives to offer an adventurous, but ultimately quite useful model was the Lost Type Co-op, founded in 2011, describing itself as ‘the first of its kind, a Pay-What-You-Want type foundry’.

Guyot, released by Retype. Design: Ramiro Espinoza, 2017.

Miraculous income

James Edmondson, who now runs the OH no Type Company, was a student at the time, combining his education with work; he recently wrote that Lost Type gave him a chance to re-evaluate his existence as an ‘unambitious, jaded general graphic designer’. He had designed a ‘simplified script typeface’ for a school project in early 2011: ‘I offered it as a free download on a website, and less than a dozen or so friends actually got it installed. A few weeks after the semester ended, I came to learn about Lost Type. I emailed the person on the about page, and Riley Cran graciously offered to host the typeface on the platform. On 5 July 2011, my phone started buzzing every few minutes with an email from PayPal saying that someone I didn’t know was giving me money for a font. I think that day I received around $700 in small donations. My world had fundamentally changed forever. I began working on other typefaces for release on Lost Type, and was generally having a great time. It quickly dawned on me that my frugal bachelor lifestyle coupled with this miraculous income afforded me the freedom to quit my day job.’

To many type designers, the popularity of systems that offer subscriptions instead of lasting licences are worrying. Flat-rate type subscriptions may yield much less revenue for the makers than actually selling the work, mirroring what has happened in music with services such Spotify and Apple Music. New initiatives are popping up on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as in India, to interest users in the new, the unusual and the unknown … with variable results.

Franklin Gothic released by American Type Founders (ATF). Design: Morris Fuller Benton, 1905, Mark van Bronkhorst, Igino Marini, & Ben Kiel, 2019.

One smart solution that looks beyond the flat-rate, catch-all subscription is Fontstand, a site-and-app developed by Netherlands-based Typotheque’s Peter Biľak and friends from former Czechoslovakia. Their model – which is like leasing with a buying option – was discussed in Eye 97. Fontstand offers the best of both worlds: it is possible to try out a font family for an hour at no cost, rent it per month at a tenth of the price, and call it yours (i.e. get a permanent licence) after a year. Fontstand offers typefaces from 56 foundries – a collection that is large and varied, but also curated – selected to represent independent type production.

There are a few new platforms which try, or have tried, to work with subscription only. Spanish company Fontown comes with an app that allows users to work with fonts without ‘owning’ them and storing them locally. They are working on a collection of new and exclusive typefaces, offering production assistance to type designers. The current collection mainly consists of existing fonts – offering alternative distribution to microfoundries – but also includes fonts that come with a Creative Commons licence and / or are available from Google; the fonts are also collected on a transparent free-fonts aggregate platform like Font Squirrel. Fontown’s founder and CEO Lole Román explained: ‘Fontown’s mission is to offer legal and easy access to any font that exists in the world, including free and open-source licence fonts.’

Over to India, where in 2017 Indian Type Foundry’s Satya Rajpurohit launched his own subscription platform, Fontstore. ITF has been quite successful providing bespoke Indic designs to major corporate clients, but also publishing Latin fonts from Europe, which did very well on supermarket platforms like MyFonts. Rajpurohit decided to build Fontstore around an exclusive collection of new typefaces, partly commissioned from young European designers. The subscription system did not yield the steady income Rajpurohit had hoped for. ‘Within a year I realised that Fontstore cannot sustain from just the subscription service and I needed to introduce other licensing options … A major difference between Fontstore and other services (Monotype and Adobe) was the exclusivity of the fonts. All the fonts that we offered on Fontstore were developed exclusively for Fontstore and these fonts were not available anywhere else, not on even ITF. But … people who subscribe to these services cared less about the exclusivity [than] the total number of fonts.’ Rajpurohit changed Fontstore's business model. ‘We are now making Fontstore a unique marketplace where users can “try, subscribe, rent or just buy” any fonts.’

Crayonette released by DJR. Design: David Jonathan Ross, 2017.

Micro power

Some people think big. Others think small but manage to create an alternative platform that attracts hundreds, then thousands of curious fans. Possibly the most impressive one-man initiative is the Font of the Month Club by Massachusetts type designer David Jonathan Ross (aka DJR). A former junior designer at Font Bureau, Ross caught the type world’s attention with designs that could be extremely practical, like the humongous Input family, a monospaced typeface for writing code, or entertaining and extraordinary, like Bungee (a free Google Font to set vertical signs and headlines) and the highly original weight/width/height-shifting FIT. In 2018 Ross, one of the most striking characters on the US type scene, was awarded the Charles Peignot Prize from the worldwide type design association ATypI, whose Twitter editor described him as an ‘innovative, kind and generous member of our community’. Ross has said: ‘There are already a ton of fonts out there to choose from. That’s why I make fonts that challenge you to set your work apart by going beyond the generic workhorses and confronting the unique visual and technical demands of your text.’

Ross created his Font of the Month Club as a personal incentive to produce work continually, a place to realise ideas without worrying about total perfection, and build a fan club that expects the unexpected. Subscribers, who at present pay $6 a month, get a new font, or a new style of an existing family, landing in their inboxes promptly on the first of each month.

The Wolpe Collection released by Monotype. Design: Berthold Wolpe, 1930s and later. Digital family designed by Toshi Omagari, 2017.

Was the invention of the Font of the Month Club triggered by a dissatisfaction with the changes in how retail works? ‘Yes, certainly. Recently, retailing fonts has started to feel kind of broken to me; I didn’t feel like I was reaching the people I wanted to reach, especially with my more experimental designs. Mega families and deep discounts do not always lead to interesting type design, and the club was an opportunity for me to step back and re-evaluate my projects,’ Ross told me. Since its start in May 2017, the Club has grown into something that pays off. ‘I’m not quitting my day job or anything, but it’s a growing source of supplemental income and I consider it to be a success.’

Another font retail experiment, Future Fonts, was conceived in the US by Portland company Scribble Tone, owned by designers Lizy Gershenzon and Travis Kochel, with help from type designer James Edmondson. Designers of the Infographics tool FF Chartwell, the pair created a new marketplace that allows young type designers to publish fonts before they are (completely) finished. Prices vary according to the state in which a font is offered.

As designer of a FontFont, Travis Kochel has been an observer of the unrest in the type world as a result of Monotype’s approach to its acquisitions. ‘I think there need to be more independent retailers out there. We’re definitely trying to position ourselves as foundry friendly. Our experience … definitely played a huge role in how we shaped the Future Fonts Foundry Agreement. But to be honest, our primary motivation was more in solving a problem with our own process, and relieving the pressure of perfection. It’s frustrating spending years working on a typeface, and having no idea how it’s going to be received. When working on custom typefaces, we often provide beta versions throughout the process. If it works in that context, why not in retail? As long as there’s transparency in the current state of the typeface, I think people are fine with it.’

Standard released by BB-Bureau. Design: Benoît Bodhuin, 2018.

Support in the community

Since its launch in early 2018, dozens of type designers, among them quite a few fresh MA graduates, have chosen Future Fonts to test out new designs, receive feedback from experiment-friendly users, and make some money in the process. Kochel: ‘A lot of them are interested in using it as a place to try out riskier ideas as well. It’s partly due to the brand we’ve been pushing, but also releasing things in progress reduces the cost of failure.’ Future Fonts is quite selective about who they let in. ‘In the early years, we’re trying to set a precedent of strong work from people we can count on to follow through. We do take submissions, and have brought in quite a few this way. For the submissions that are easy yeses, we just handle [these] among the three of us. For those that we’re on the fence about, we often run them by the current members to get their input.’

Future Fonts’ library now comprises around 40 microfoundries, with two or three added each month. Kochel said that the platform has received 4500 orders over the past year – about half of them in the fourth quarter, which sounds pretty healthy. Meanwhile, Future Fonts is managing to build a community of users and makers. ‘It feels like we’re bridging a gap between the customers and designers. We also have a Slack group for all the designers on the platform, and it’s become a super-supportive creative community, which feels pretty special.’

I ended my review of TYPO Labs last May by expressing my hope that such corporate-sponsored conferences would continue to offer a platform to young designers with ideas that challenge the establishment: ‘The independent young wolves and whelps are the lifeblood of the type world.’ This didn’t happen but it is encouraging that small, flexible and intelligent initiatives keep the type community alive and kicking.

A2 Record Gothic released by A2-Type. Design: Henrik Kubel, 2019.

Jan Middendorp, designer, writer and author of Dutch Type, Berlin

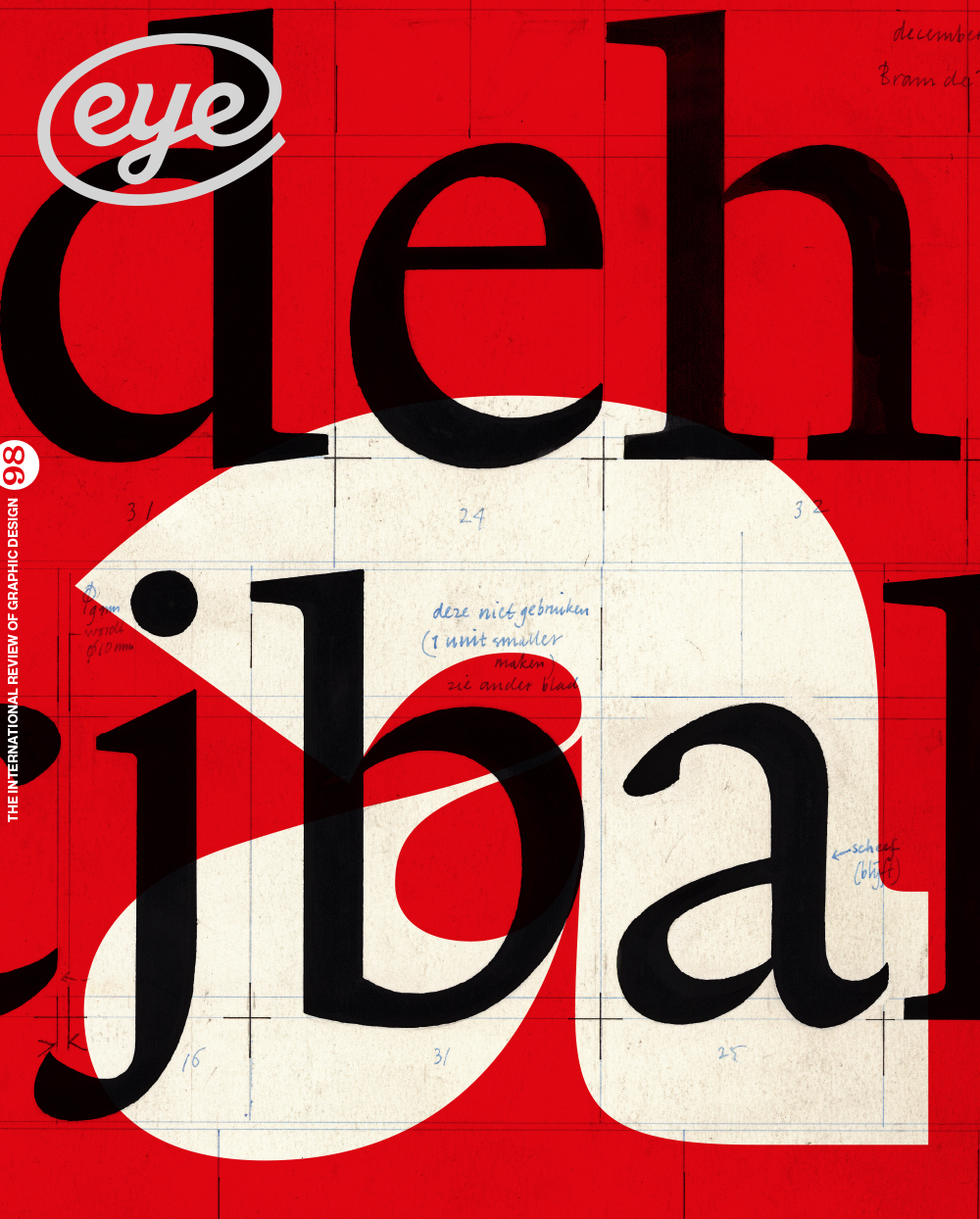

First published in Eye no. 98 vol. 25, 2019

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 98 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.