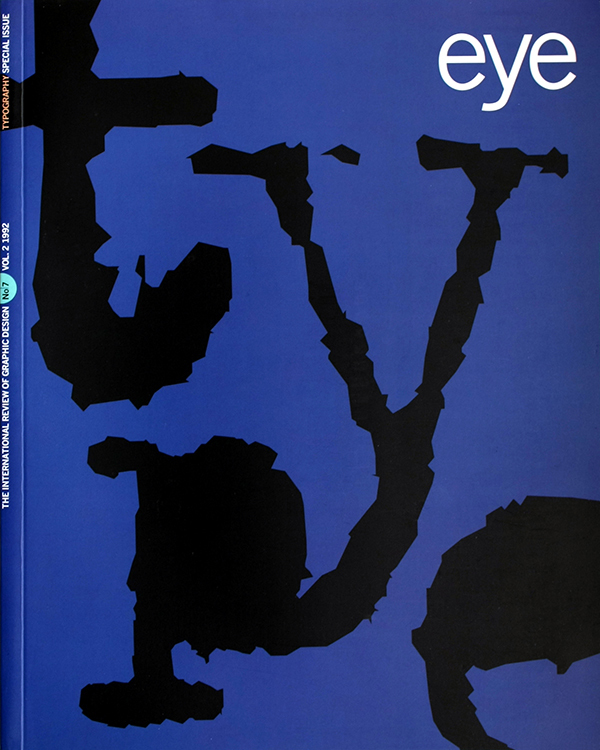

Summer 1992

Type as entertainment

Why Not Associates are the wild boys of the British typographic scene … How do they get away with it?

In less than five years as a formal partnership, Why Not Associates have come to occupy a pivotal position on the experimental wing of British graphic design. They are leading figures among a handful of London-based companies increasingly perceived on the larger international stage to represent a new wave of energy and invention in British typography and graphics. While the most obvious point of comparison, 8vo, produce a progressively more mutated version of Swiss Style, which stands out in the British context but offers fewer surprises to Europe and the US, Why Not’s inspirations are more firmly rooted in local traditions and culture.

The question Why Not’s three partners – Andy Altmann, David Ellis and Howard Greenhalgh – are most often asked is how they get away with it. Altmann and Ellis, the team’s graphic designers, routinely pull off visual stunts that more cautious contemporaries assume would send their own clients into shock. Why Not designs are constructed from frantic scribbles, arbitrarily chosen images and weird typographic mechanisms that look like something Jean Tinguely might have dreamed up on a day off from making auto-destructive sculptures. As a result, Why Not have a reputation for craziness and pleasing themselves that is not wholly borne out by more recent projects, or by the statements of the designers themselves. In that sense, their choice of name – a jibe from their student days that doggedly stuck – is already coming back to haunt them. It is undeniably memorable and, as Altmann says, “one of the few graphic design company names that professes an attitude”. But it also sounds jokey and glib. “What it really means,” says Ellis, “is that you shouldn’t have to account for every single mark you make.”

Why Not’s willingness to trust their own instincts, and quietly insist that their clients do the same, has distinguished their work from the start. They moved from St Martin’s to the Royal College of Art – Ellis in 1984, Altmann in 1985 – because “At St Martin’s, at that point,” remembers Altmann, “the type was the line you put under the idea. A ‘joke’. Bob Gill. People were still doing that kind of stuff.” Herbert Spencer’s Pioneers of Modern Typography, on the other hand, confronted them with an alternative tradition of heroic experiment. From Piet Zwart in Pioneers to Gert Dumbar, their new professor at the RCA (whose freewheeling creativity had first impressed them at a lecture at St Martin’s) the emphasis lay on the expressive integration of image and type.

By the time they graduated in 1987, Ellis and Altmann had convinced themselves they were unemployable. “We certainly didn’t want to work for anybody else,” says Ellis, “and I couldn’t think of any London studio that would let us do the kind of work we wanted.” Luck intervened when Greenhalgh, a fellow student, came to them with a magazine project for the US cosmetics company Sebastian. Other commissions followed and within six months the decision was taken – “It just sort of happened,” says Altmann – to form a partnership. Greenhalgh later set up the film side of the enterprise.

Their clients since then have embraced both commerce (the clothing retailer next, Smirnoff vodka) and culture (exhibitions on the Situationists a the Pompidou Centre, Paris, and on avant-garde Japanese architecture). Unlike an earlier wave of British designers reacting against the mainstream, Why Not have shunned the potential ghetto of the record sleeve; it is an outlet they hardly need when their existing projects have proven so rich in opportunities for self-expression. They resist the suspicion, though, that this is their primary motivation. “We wanted to produce work that was self-expressive, but also solved the client’s problem,” says Altmann. “You might as well be a painter if you are not solving the client’s problem.”

In common with other members of their generations, Altmann and Ellis argued that many of the conventions of conceptual graphics, however successful in the past, are no longer enough. They believe that a visually sophisticated audience needs, and expects, rather more. The painterly quality of Why Not’s work is their way of drawing viewers into the message and holding attention: a retinal reward. In the case of the Next mail-order directories, the “message” was more a matter of lyrical image than literal communication. These chaotic covers and volatile divider pages, which appeared to be in the grip of typographic Big Bang, were their most notorious example to date of what Altmann calls “type as entertainment”.

As Why Not develop, the essential Englishness of their design – a quality shared by some of their closest associates – is becoming clearer. As with Phil Baines (their contemporary at the RCA) and Jonathan Barnbrook (who worked with them on a Next directory) there is a love of ornamental complexity that throws out echoes of Gothic architecture, illuminated manuscripts, even the Arts & Crafts tradition. Why Not’s two most significant projects to date, both remarkable instances of their assimilation into the professional mainstream, enshrine fundamental polarities of English cultural life – individualistic rebellion and a love of pomp and circumstance – that the social commentator Peter York once summarised as “Punk and Pageantry”. In their postage stamps commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the Queen’s accession, and their identity for the Hull 1992 Festival, their existing graphic repertoire found a perfect, through improbable, match in the deep traditionalism of the subject matter.

Why Not confess to having been “flabbergasted” when they received a call from the Royal Mail asking them to go ahead with their invited proposals for five first-class stamps. Yet the overriding impression of regal dignity and human warmth was a keenly judged answer to the brief. The expected Why Not-isms take the form of broken silver borders with steps and curves, and a network of filigree rules that links typographic elements within the stamps and connects them when seen as part of a sheet. These elements combine with heraldic devices carefully muted on the Quantel Paintbox to create a jewellery box-like setting that vividly conveys the Queen’s status as national treasure. With the Hull Festival project, Why Not had another unexpected chance to apply the graphic language they have developed in earlier project to a more precisely defined set of problems. Their clients were fifteen bluff Yorkshire councillors with a reputation, among local designers, for conservative taste. At the core of the festival’s graphic programme, the council hoped to find an identity that the city could use after the festival was over. “The last thing they wanted was a single logo to be slapped on everything,” says Ellis. “It needed to be adaptable and malleable.”

The starting point for the programme is an “H” (for Hull) with the bar replaced by five arrow-tipped vertical strokes – a stylised portcullis that evokes the city’s past and symbolises the council’s conception of both city and festival as a “gateway to Europe”. These few simple elements provide the graphic vocabulary and typographic framework for the festival’s posters, brochures, maps, shopping bags, street signs, invitations and stationary. Even when they are used in their most exploded or dissected forms, it is still easy to recognise the festival’s identity, reinforced by the bold use of turquoise, a reference to the verdigris on the copper roofs of the city’s buildings. The typographic itself, Eric Gill’s Perpetua with a smattering of Gill Sans, like the project as a whole, is both traditionally English in mood and austerely modern in its asymmetry.

Why Not won the Hull project, one of the councillors told them, by being the most “down to earth” designers in the way they presented their ideas and work. Here, it seems certain, lies one of the reasons for their commercial survival against the odds. Not only are they blessed with the popular touch, but they genuinely believe it should be possible to have their creative cake and eat well on it, too. Unlike the American deconstructionists, with whom they are sometimes bracketed on stylistic grounds, Why Not adhere to no discernible theoretical programme. Disjointed and strange as their solutions might look to some eyes, Why Not justify their visual strategies (though only up to a point, of course) in the most conventional, and modest, of professional terms.

“I think our work is funny,” says Altmann, and perhaps it is, in a Monty Pythonish way. Lurking beneath the surface, and occasionally breaking through in more personal projects, is a taste for daft music hall song lyrics and word-play, and the surreal catchphrases of stand-up comedians like Tommy Cooper, and Morecambe and Wise. From this unlikely stew of schoolboy influences, and their later experiences at college, Why Not have forged a graphic attitude and method that looks utterly contemporary, while retaining its ties with the past.

“Our work is going to date,” concedes Altmann. “My god, it’s going to date!” “But that’s one of the nicest things about graphic design,” counters Ellis. “You pick up a piece of 1950s graphics and you marvel at it because it represents a whole other language.”

First published in Eye no. 7 vol. 2, 1992

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.