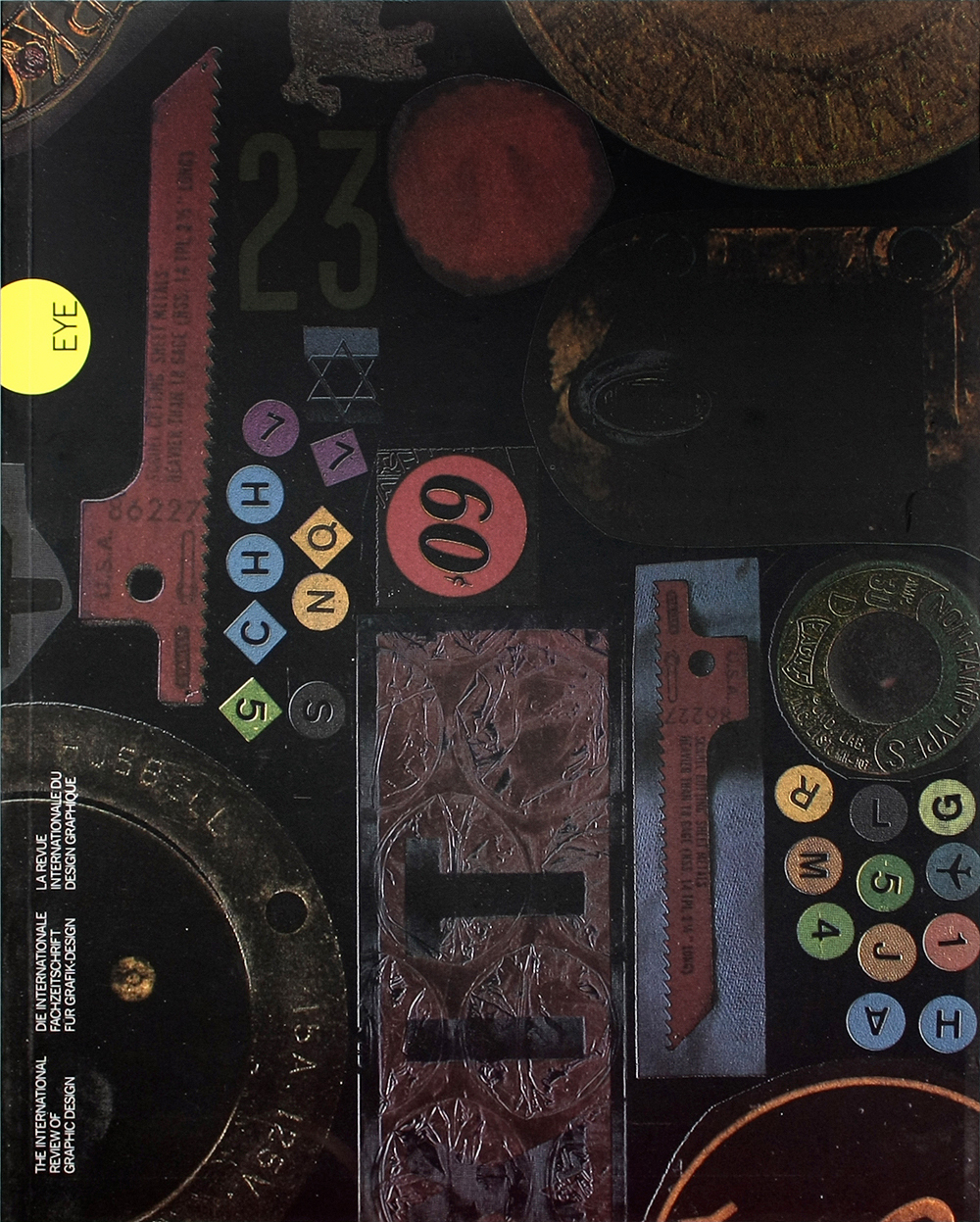

Winter 1990

Design from the margins

America-Holland: Overseas Visions

Gemeentemuseum, The HagueIt was probably close to midnight when Gert Dumbar, a key figure in the “America-Holland: Overseas Visions” symposium held in The Hague in October 1990, rose to address US graphic designer Art Chantry from one of the microphones placed around the auditorium. Speaking at the end of an evening’s discussion of socially-oriented design, Dumbar conveyed in a few words the most crucial difference between the US and The Netherlands: “You live in a country of money; we live in a country of subsidies.”

Seattle-based Chantry has concentrated his design efforts for many years on drawing the public’s attention to the ideas of the issue-oriented, non-profitmaking organisations he believes in. Often employing low-cost production techniques, his work – approximately one-third of which is undertaken unpaid – avoids prettiness in favour of an expressive, experimental approach that couples form with content.

Chantry, who places “appreciation by the common man” before traditional aesthetic criteria in judging the success of his work, was joined in front of the hall by his Dutch counterpart for the evening, Rob Schröder of Wild Plakken, a design collective known for its socially and politically critical attitudes. The loosely monitored panel discussion had compared the current apathy to social causes found in many of today’s job- and money-hungry designers with graphic design of the 1960s and 1970s, informed by the more turbulent politics of Europe and America in the period.

Organised by Theatre Zeebelt and Studio Dumbar with financial support from the Ministry of Culture and private Dutch firms, “America-Holland: Overseas Visions” paired four American and four Dutch designers who share an active interest in a particular aspect of graphic design. Design critic Steven Heller, art director of The Sunday New York Times Book Review, introduced each of the topics and provided additional commentary. Heller chaired the panel discussions with Pieter Brattinga, who has own widespread respect for his ambassadorial efforts on behalf of the graphic design profession in The Netherlands.

In one session, Hungarian-born Tibor Kalman of the New York design firm M&Co. discussed the vernacular in graphic design with Pier Schreuders, who is known for Poezenkrant, the journal about cats which he began in 1974, and his work for cultural clients such as Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum. Another pairing consisted of David Frej of Chicago and Gert Dumbar, of Studio Dumbar, both of whom began their careers as fine artists. Studio Dumbar’s clients range from small cultural organisations to large corporations and commercially-targeted institutions; the work they produce is considered to be inventive and experimental, if not controversial. Dumbar says: “I sometimes borrow ideas from the laboratory of art and try to implement them in my work. I believe that a new direction in graphic design will be inspired to a great degree by the surprising and unpredictable element of fine art.”

Graphic design and the computer was the subject of a discussion between April Greiman of Los Angeles and Jelle van der Toorn Vrijthoff, creative director since 1984 of Total Design in Amsterdam. The two designers approach the computer in different ways. Greiman, whose work grew out of the Southern California New Wave style of the late 1970s, described her “hybrid” approach as using “a variety of tools and techniques and disciplines that range from manual to computer-based”.

While Greiman has integrated technology into the design process, van der Toorn Vrijthoff believes that the computer is best left for the weeks of production that follow the relatively short creative stage. One of the few Dutch design firms committed to the large-scale use of computers, Total Design has more than thirty Macintoshes and three very costly Aesthedes, one of the most sophisticated design workstations. Seated alongside van der Toorn Vrijthoff, Greiman expressed her fear “that everyone trying to reach perfection will use the computer to duplicate the past,” meaning what can be done by handwork, rather than allowing “chance accidents to bring about some of the most exciting discoveries in the design process.” Though van der Toorn Vrijthoff strongly disagreed, some members of the audience used Greiman’s remark to criticise Total Design’s faded image over the last decade.

At this point Dutch audience and American guest appeared to share common ground; at other times the gulf between the two design cultures appeared to be wider than one might have expected. The Dutch showed little patience when confronted by tales of the pressures of a capitalistic society. In a “country of money”, graphic design springs most directly from the worlds of advertising and promotion; in a “country of subsidies”, its roots are to be found in painting and drawing. In the US the focus is too often on the large scale of the mass-market; in The Netherlands it is usually on the individual.

First published in Eye no. 2 vol.1 1991

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.