Winter 2017

The crew with no name

Ravilious & Co: The Pattern of Friendship

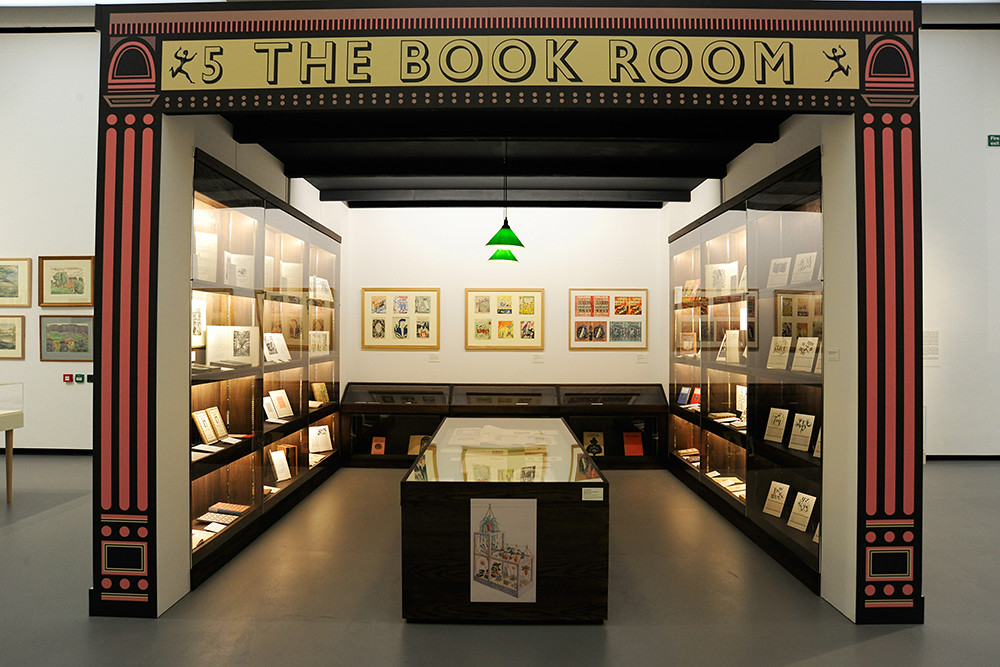

Towner Gallery, Eastbourne. 27 May – 17 September 2017. Curated by Andy Friend. Exhibition design by Webb & Webb.

This ambitious exhibition throws light on a circle of artists and designers grouped loosely around Eric Ravilious (1903-42). In Eastbourne’s Towner Gallery there were more than 500 artefacts; in Sheffield’s smaller space there are still more than 400. Ravilious, Edward Bawden and the Nash brothers Paul and John have had their work and lives reasonably well documented, but Andy Friend’s curation puts them into new contexts. Others, including Ravilious’s wife Tirzah Garwood and his on-off mistress Helen Binyon deserve further attention. Other characters in Friend’s survey include Peggy Angus, Douglas Percy Bliss, Barnett Freedman, Thomas Hennell, Percy Horton and Enid Marx.

In addition to these artists and designers, arts mandarin Kenneth Clark, Morley College principal Eva Hubback, Architectural Review editor J. M. Richards (author of High Street), Royal College of Art principal William Rothenstein and the founders of the Dunbar Hay shop play crucial roles, too. This touring exhibition is a welcome chance to fill out their interconnecting stories, to understand the context of the time, and to see impressive work that has hardly been exhibited since the 1930s.

For example, a twelve-minute film of the Morley College commission by Bawden and Ravilious is essential viewing, since it collates all the existing photos of the college’s Refreshment Room murals – destroyed by bombing in 1940 – alongside studies and preparatory artwork. A ‘bookshop’ installation shows a large number of book illustrations and covers designed by their circle of friends, including Ravilious’s own wood engravings for the Monotype 1933 calendar. Webb & Webb use some of the motifs from this as a device within their exhibition design.

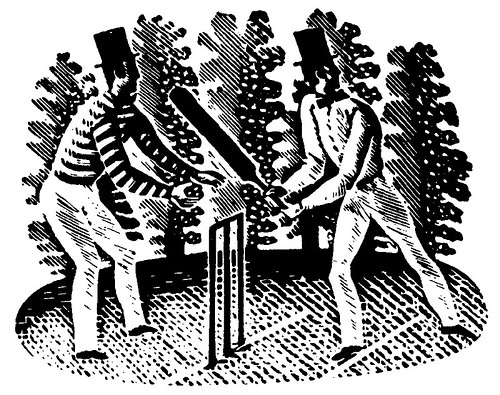

Elsewhere in the show, Friend’s curation emphasises the importance to this circle of artists of shrewd clients: The Listener, the Curwen Press, Lanston Monotype, Kynoch Press, London Underground, Wisden and many more. Display type on the wall quotes Tirzah Garwood’s delight at her first commission for the BBC in 1928: when asked to do her first job, she ‘danced round the room with joy’. Garwood (1908-51) had been a precocious illustrator, who studied with Ravilious when she was a teenager. Her first wood engravings from 1926 are, in Friend’s words, ‘evidence of how, in a difficult art, Tirzah almost instantly became an adept peer of her already accomplished teacher – and during 1927 began to exert an influence over his own approach.’

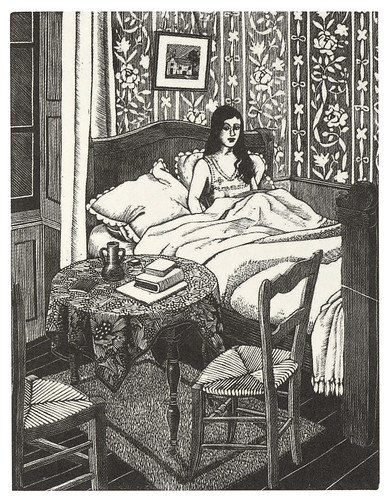

Right. Tirzah Garwood, The Wife [a self-portrait], 1929.

The relatively small amount of work by Garwood after her 1930 marriage to Ravilious reflects several things: the economic turndown; the lack of opportunities for women; the demands of family (three children and a wayward husband); and cancer. Her late paintings, made after a happy second marriage and the return of the disease that would kill her, show another side of her prodigious imagination, while her early engravings and watercolours have an ease with human form that took Ravilous longer to acquire, and a sharp humour all her own.

Little known work by Helen Binyon, including some charming children’s book illustrations, added further layers to the exhibition’s documentation of this fascinating group of pragmatic artists. Alan Powers, in his introduction to Friend’s book Ravilious & Co, compares them – as a prolific, interconnected and ultimately influential group – to the Pre-Raphaelites. But he notes that their lack of an easily referenced group name might ‘partly account for the long time it has taken for them to be recognised’.

Barnett Freedman’s work is better known, but the chance to see so much of it in one place is a delight. One ‘scoop’ of the exhibition is the portfolio of student work with which Freedman, who had suffered several rejections for a London County Council (LCC) scholarship, doorstepped Rothenstein. The latter quickly made sure the young artist was offered both a place at the RCA and a three-year LCC grant. During a tour of the Towner, Friend claimed that Freedman was a talented painter, but a ‘lithographer of genius’. Plenty of evidence backs up this claim, with posters, advertising and book covers from several stages of his regrettably short working life. A short film, with music by composer Benjamin Britten, shows Freedman tackling a stamp design commission, including a rather staged conversation with a Post Office official.

Friend also fights Ravilious’s corner, giving no credence to J. M. Richards’ comments (in his 1980s memoir) that the artist was running out of steam by the early 1940s. The ‘Submarine’ lithographs and the hallucinatory watercolours of military men, equipment and aeroplanes (such as Hurricane in Flight, 1942) support Friend’s view that Ravilious was still learning, growing and stretching his abilities when the plane carrying him failed to return in September 1942.

Wood engraving designed by Eric Ravilious for the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, 1938, and still in use.

Top: Installation view of ‘Ravilious & Co’ at Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne, 2017. Exhibition design by Webb & Webb. Photograph: Alison Bettles.

John L. Walters, editor of Eye, London

First published in Eye no. 95 vol. 24, 2018

Ravilious & Co: The Pattern of Friendship, also at the Millennium Gallery Sheffield, 7 October – 7 January 2018 and Compton Verney Art Gallery, Warwick, 17 March – 10 June 2018.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 95 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.